When we launched a paid version of iDoneThis, we held our breath — we didn’t know if a single person would sign up.

The waiting, the sweat, the nerves.

Finally, the whoosh of a collective sigh of relief. One trailblazer of a person signed up for iDoneThis and put their credit card down.

Amidst all that “will they pay?” jitters though, we figured that if just one person signed up, there had to be at least 1,000 more people out there who hadn’t yet heard of us that would be willing to do the same. And that first month, we got $1,000 recurring revenue signups for our service.

How We Did It

1. A simple product with a straightforward value proposition.

From the beginning, iDoneThis has been simple to explain and understand:

We send your team a daily email asking, “What’d you get done today?” You reply. The next morning, your team gets an email digest with what your team got done yesterday — to kickstart another productive day.

It’s an incredibly simple way to sync up at work.

For almost every team, syncing up is a pain point, and we provide a simple solution: instead of having meetings or interrupting people who are trying to get things done, sync up asynchronously over email.

The reason that it can be harder to build a simple product is that you will always have people laughing at you, asking incredulously, “People pay for that?” This happened non-stop in the early days of iDoneThis and continues to happen today.

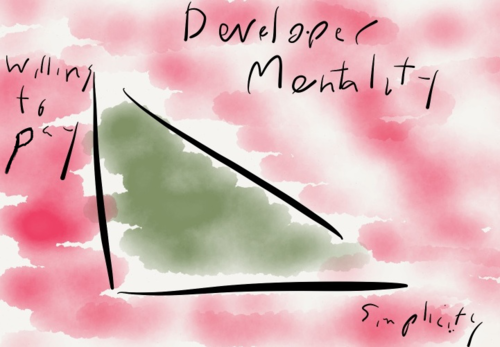

In fact, the developer mentality is that the simpler a product is, the less willing people are to pay. Why? Because if a product is simple, developers will build it themselves instead of paying for it.

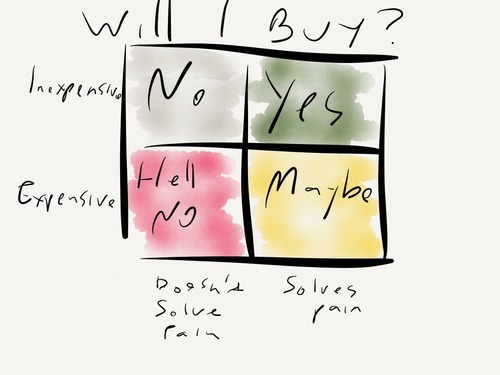

But it turns out that what people really think when considering a purchase decision is, “Does this solve my pain point and is it not outrageously expensive?” rather than “Can I build this myself?” Most people — and this includes developers — want to focus on doing their actual work, not building and maintaining a piece of technological scaffolding.

If you address a straightforward pain point in a simple way, people are more likely to understand that you solve their problem, and are thus more likely to buy.

2. Avoid the cold start problem.

During the month that we got to $1,000 in recurring revenue, we actually did very little in the way of customer acquisition.

We could’ve gotten to $1,000 in recurring revenue by sitting around and doing nothing all day, because we’d already done the work up front to build an audience.

By that point, iDoneThis for personal, self-tracking use had grown to some 40,000 members, so there was considerable inbound traffic to the site. While the conversion rate was low because people arrived expecting to see the personal product, we nevertheless knew that people were coming to our page in the first place with a willingness to check out our wares.

Plus, we’d previously had individual members request that we build a team product, so we had a list of people to contact about the new paid version.

As Paul Buchheit, creator of Gmail and partner at Y Combinator, says, the correct order of operations is to “sell before you build.” When you launch, you want a whole list of people that you can tell to buy it. But more than that, you want to ensure that you’re investing all that time building something that people want to buy.

If you can’t build that list of interested people, it’s a pretty good sign that you shouldn’t build the product you have in mind at all.

3. Minimum viable monetization.

Before launching the paid version of iDoneThis, we had endless conversations about how the pricing plan would work. Would we have tiered plans, price per user, price per usage, etc.? It felt like we’d never launch the paid version because we’d never figure out pricing.

It’s easy to get caught up in the anxiety of selling a product for money because you never fully believe that someone is willing to pay for it — that is, until someone does. That means that the most important thing you can do with pricing is to get going with the minimum scheme you need to charge people and make money.

We chose a very simple plan of monetization of $3 per person per month, then later changed that price and grandfathered in all the old teams.

We also decided to take peoples’ credit card up front. The idea was to test the question of whether people were willing to pay in the harshest way. We felt like people must really want the product if they were willing to put their credit cards down for a free 30-day trial period. And we’d know within the first month whether people were willing to pay instead of having to wait the 30-day conversion period.

By requiring a credit card up front, we also didn’t have to build all of the infrastructure for pinging people to put down their cards during the conversion period, which was just another barrier to getting the paid product out.

Despite the overwhelming uncertainty that we felt about convincing people to get out their credit cards, we’d actually prepared for much of the guessing game by doing a lot of legwork, cultivating engagement and paying attention to feedback, and testing for customer enthusiasm.

When you know you have a simple solution to an existing pain point, have put in work on selling before building, and go ahead with pricing structures and processes that also uncover information about your market — the sweat and the nerves will probably not go away — but you’ll have a sense of underpinning and foundation to get the ball rolling.

Liked this article? Sign up for our free newsletter for more great content on startups, productivity, and management.