When did work become so noisy?

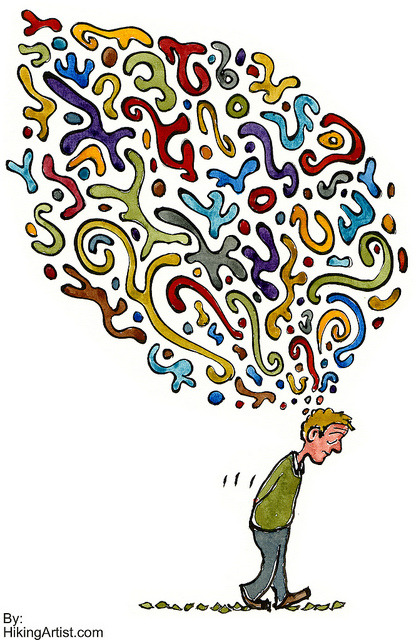

I don’t just mean the ambient noise, that clickity-clackity typing, strangely noticeable chewing, annoying finger tapping, and chit-chatting hubbub of an open floor plan office. I’m also talking about the information and social inundation invading our work life, the buzzes and pings, the tweets and likes, the emails and comments, the meetings and chats.

Our notion of productivity has become imbalanced toward focusing on the inbox of our thought process — input, information, inspiration. I can feel productive after scanning tweets, reading articles, even having an inspiring conversation, but if I don’t take time to think and process, if I don’t actually turn the input into something, that feeling is illusory.

Ultimately, productivity requires producing, creativity creating. It sounds so simple and obvious, but it has been easy to forget these days that we need solitude, quiet and time.

The Need for Solitude Away from Work Noise

We need more of what Paul Graham has identified as maker’s time versus manager’s time. Makers need uninterrupted blocks of time to create and make progress in their work, the kind of schedule that resists carving out units of time for discrete tasks. For a maker, a meeting can disrupt and derail a whole day’s work.

The difference between makers and managers is not just in type of schedule, but more basically, in the nature of their work. Makers require solitude and quiet while managers require interaction and conversation. Solitude is necessary to create, to pay attention to yourself, to tune into what psychiatrist T. Byram Karasu calls your internal rhythm or music. Tuning in allows “time for previously unrelated thoughts and feelings to interact, to regroup themselves into new formations and combinations.”

Similarly, the late psychologist Ester Buchholz explains:

Solitude is required for the unconscious to process and unravel problems. Others inspire us, information feeds us, practice improves our performance, but we need quiet time to figure things out, to emerge with new discoveries, to unearth original answers…. The natural creativity in all of us—the sudden and slow insights, bursts and gentle bubbles of imagination—is found as a result of alonetime. Passion evolves in aloneness. Both creativity and curiosity are bred through contemplation.

Apple’s Steve Wozniak, too, champions alonetime for the sake of the creative process:

Most inventors and engineers I’ve met are like me — they’re shy and they live in their heads. They’re almost like artists….And artists work best alone — best outside corporate environments, best where they can control an invention’s design without a lot of other people designing it for marketing or some other committee.

Woz’s point isn’t just relevant to artists, inventors, and engineers, nor is it correct to say so broadly that the only and best way is to work alone. It highlights how privacy, solitude, and autonomy are needed to get stuff done by limiting inputs that can reach the level of buzzy work noise, the committees and groupthink and interference that restricts and interrupts innovation and creativity. Without some quiet, how can you listen to what’s in your head, let your own thoughts network?

Yet many of today’s business software and apps, while intending to make getting work done easier, are often disruptive. Real-time activity feeds, like Yammer, ironically mirror the addictive features of Facebook and Twitter. Online gatherings via text, voice and video chat work essentially as meetings without end. They demand the kind of time and attention that are antithetical to the maker’s schedule and make it difficult to hear and tune into yourself. Plugging in and collaboration is important but not as a continuous stream that burbles at the expense of actually producing and creating.

Quieter Frequencies

It’s not enough to point out how the work noise of our information and work culture has created what Herbert A. Simon called a “poverty of attention,” nor does it make sense to get off the grid altogether. Instead, let’s tune into quieter channels that support the reflection and contemplation that enables us to better create. Harvard Business School professor Teresa Amabile and psychologist Steven Kramer, for example, have found that maintaining a work diary cultivates a practice of reflection and translates into engagement, motivation, and a positive impact on creativity, productivity, and commitment.

We think it’s possible to provide web services that run on these quieter frequencies (though we want to find the right balance between serving both maker and manager, roles that aren’t mutually exclusive of each other in the workplace). We’ve declared that iDoneThis is part of the slow web movement, because we want to encourage reflection and emphasize doing, to enrich our attention and help people turn toward meaningful engagement. Slow web, as Jack Cheng has so insightfully written, is:

Timely not real-time. Rhythm not random. Moderation not excess. Knowledge not information. … It’s not so much a checklist as a feeling, one of being at greater ease with the web-enabled products and services in our lives.

While fast web is more about unfiltered consumption and real-time updates, slow web gives you some space and autonomy on how and when to engage, with timely interactions that “happen as you need them to happen.”

Finding Joyful Flow at Work

The value of slow web can be easier to see in our personal lives. In that sphere, we risk losing time and attention for the people and pursuits we love when we crave those hits of fast web.

Still, in our work, we risk losing relevance and development of skills that we’ll need to stay competitive. The unfolding of what Dan Pink describes as the Information Age into the Conceptual Age tracks the shift in qualities that will be required more and more in our work, adding to the traditional left-brain skills of reasoning and logic that have so pervaded the professional working landscape the right-brain skills of creativity, synthesis, and meaning. “In a world upended by outsourcing, deluged with data, and choked with choices,” he writes, “the abilities that matter most are now closer in spirit to the specialties of the right hemisphere – artistry, empathy, seeing the big picture, and pursuing the transcendent.”

In this data-deluged, choice-choking environment, we also compromise ourselves and our capability to become lost and absorbed in our work. We mess with our flow, that “in the zone” state of being where your mental energy and attention snap into focus, and you experience joy.

Pico Iyer in his lovely piece about the joy of quiet describes the paradox of technology, how what “made our lives so much brighter, quicker, longer and healthier … cannot teach us how to make the best use of them.” We can make better use of technology and information not only in our play but also our work. If we can tap into quieter channels and slower web, whatever it is that helps us really listen to ourselves, we fuel a burning flame, we build momentum, we help the maker make, we find more joy.

Liked this post? Subscribe to our newsletter for more great content on productivity, management, and how we work!