There’s probably been some time in your life when you’ve been just a touch surprised that you haven’t been hoisted upon shoulders and celebrated with cheers for your great achievement — whether you go as far back as that group English assignment making a diorama about summer reading or yesterday’s big client presentation.

Or maybe you’re more familiar with that fake almost-smile, as Joe Shmoe stood up to cheers and beers and pats on the back, leaving you amidst the ghosts of the hours of sweat and tears you put into the work.

It happens, and it stinks. But then again — we’re actually all credit hogs in our heads.

When you’re on a team, you don’t have an accurate sense of the proportion of your contribution. It’s just not that straightforward, because what happens in your very smart but usually selfish mind is that you underestimate your teammates’ contributions and overestimate yours.

Self-Inflating the Numbers when You’re Keeping Score at Work

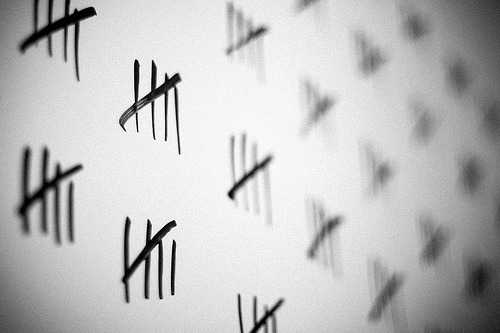

If you asked every person in your group to judge the percentage of their contribution on a project or collective task, the sum will likely add up to more than 100%.

Let’s enter some prickly relationship territory and see what would happen if you asked couples the same thing. In a famous study from 1979 by psychologists Michael Ross and Fiore Sicoly, married couples completed questionnaires on the extent of each partner’s responsibility for twenty different activities, from childcare, cooking and cleaning, planning activities, making decisions, and causing arguments.

Nearly three out of four couples overestimated their contribution, adding up to more than 100%.

Similar overallocations have been demonstrated in fundraising, academics, and in a more recent Harvard study by Eugene Caruso, Nicholas Epley, and Max Bazerman, in which MBA students estimated how much of the collective work they’d done in their study group. The sum of the students’ self-centered estimates? 139%.

I’m Always On My Mind

So what’s causing the rift between perception and reality? It’s a cognitive bias called “availability bias”, which causes you to overestimate based on what’s most striking, or available, to your mind. Personal experiences are especially salient and memorable simply because they’re yours — and this causes issues in all collaborative contexts.

Easy access to your own thoughts and knowledge about yourself, as compared to the thoughts and knowledge of others, skews your belief about the frequency and significance of everyone’s contributions. And this can have a harmful effect on how people collaborate.

While the Harvard researchers, in a related study, also saw similar overcrediting-self behavior from academic authors in shared research projects, they also found the more the authors over-credited themselves and the higher the sums went over 100%, “the less the parties wanted to collaborate in the future.”

In the initial rounds of the 1979 study, Ross and Sicoly had asked the couples to give percentage estimates of contribution, which apparently were easy to remember. Perhaps not surprisingly, this produced “a strong source of conflict between the spouses” in postquestionnaire numbers comparisons.

Unpacking the Work

The problem when it’s so much easier to remember what you’ve done than what other people have is the increased potential to provoke resentment — and ultimately disengagement if it’s a chronic suspicion — from feeling like you’ve done more than your share, or that your work isn’t being appreciated.

The Harvard researchers found that taking time to consider other people’s efforts before your own helps to align your perception closer with reality. For example, when the MBA students were asked to think about the contributions of each member in their study group as well, the sum total of their estimates was 121%. They still exhibited the cognitive bias, but it was mitigated by what the researchers call “unpacking the work.”

How to Battle the Bias with Transparency

At the heart of collaboration’s availability bias is the general difficulty in grasping what everyone on your team gets done, a natural information discrepancy that arises as a result of working with others.

Do Things, Tell People: Considering other people’s contributions is one step in the right direction. Even better is if everyone communicates about what they’ve done and showed their work for a comprehensive perspective. It’s why many teams have status meetings and standups — to not only come together to figure out how best to move forward, but in doing so, chipping away at the information discrepancies and biases that can creep into your thinking and hinder productivity.

Being transparent about what you’re getting done everyday helps prevent skepticism and suspicion among your own teammates and the skewed motivation and decreased engagement that can result from simmering feelings of isolation, resentment, and plain unawareness of what’s going on. For instance, when Michelle Sun, an engineer at Buffer — whose distributed team members share what they accomplish every day — learns what everyone has gotten done, she “understand[s] what teammates are working on, and … I feel connected with the team.”

It’s beneficial, even productive, to make your accomplishments visible, instead of hiding away keeping mental score. Understanding what everyone is doing means that you’re not worried about percentages and brownie points but focusing on getting awesome things done together as a team and aligning the points between individual and collective progress and meaning.

Liked this post? Subscribe to our free newsletter for more great content on productivity, management, and how to work better!

Images: [1] Robert S. Donovan; [2] Ken Teegardin.