I was talking to a friend, who is an attorney, some years ago. We were discussing a small disagreement I was having with a coworker. The friend gave me some advice that I’ve practiced ever since.

“Have him send you an email. Make him write out exactly what his request is.”

Lawyers love this technique, he told me. And the benefits are two-fold.

For one, writing forces clear thinking. It will become obvious if someone doesn’t have a clear idea what they’re asking once they try to put it down on paper. And secondly, should some disagreement on the topic come up in the future, you will have a clear record of what was said and when. There will be no squabbling over who said what.

You should know how you can deal with awful coworkers by getting things in written.

It’s an amazing tool that can make a big difference in your personal and professional life. The phrase “get it in writing” often conjures thoughts of a lengthy contact, formal documents with signatures and lawyers involved. It doesn’t have to be that way. “Get it in writing” can be something as simple as an e-mail.

If used effectively, it’s a practice that can stop workplace conflicts before they even show up. Think about how many disagreements in the workplace are some version of this conversation.

“You said X.”

“Well I said Y.”

“I thought you meant Y first, but then X.”

“What I meant was Z first then X, never Y.”

It’s a mess. It can be avoided. All we have to do is respect the power of getting things in writing.

Writing forces clear thinking

We’ve written before about how the best leaders harness the power of written communication.

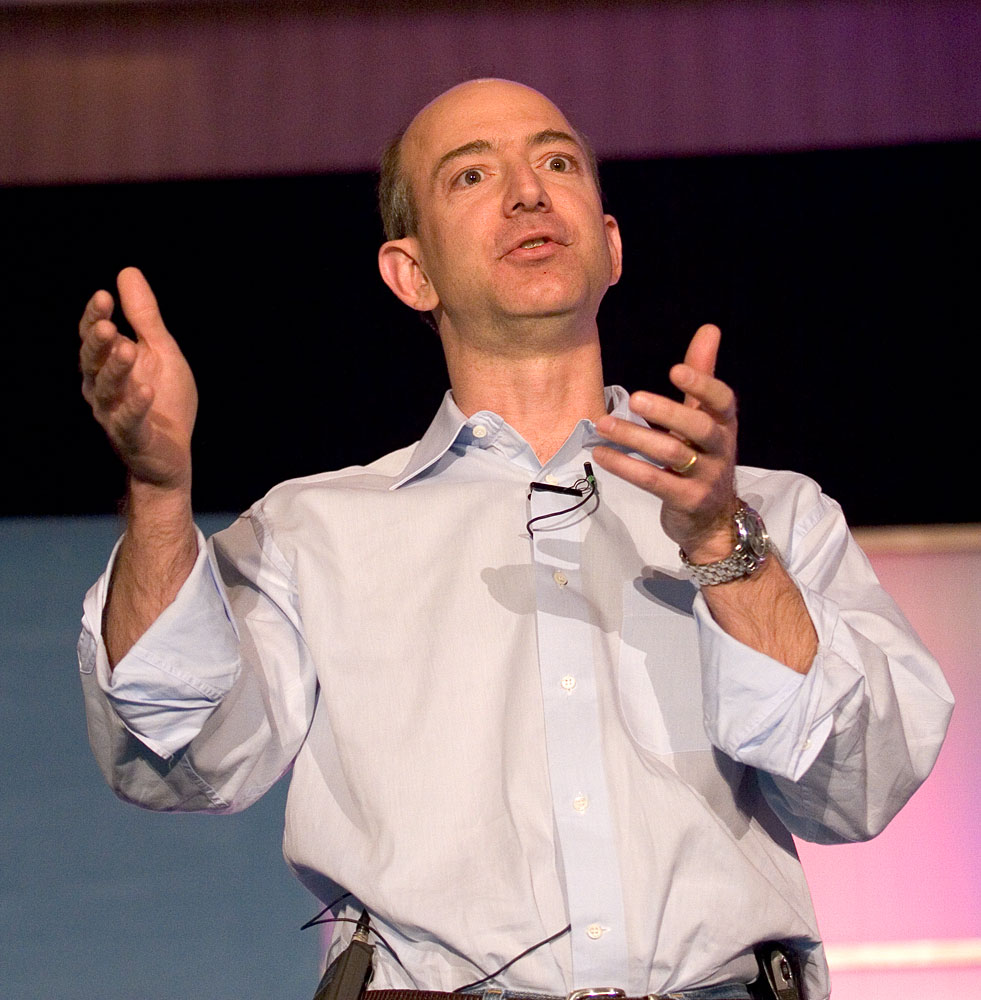

Amazon Founder and CEO Jeff Bezos values writing over talking so much that in Amazon senior executive meetings, “before any conversation or discussion begins, everyone sits for 30 minutes in total silence, carefully reading six-page printed memos.”

“There is no way to write a six-page, narratively structured memo and not have clear thinking,” Bezos has said.

Former Intel CEO Andy Grove calls writing “a safety-net” for your thought process. Grove also found having managers write reports at Intel forced the manager’s thinking to be more precise.

“As they are formulated and written, the author is forced to be more precise than he might be verbally,” Grove wrote. “Hence their value stems from the discipline and the thinking the writer is forced to impose upon himself as he identifies and deals with trouble spots in his presentation. Reports are more a medium of self-discipline than a way to communicate information.”

And more precise communication, as you can imagine, leads to less misunderstanding down the road. Less misunderstanding leads to less conflict. Less conflict leads to more time serving the mission of the company, less time putting out fires.

Or as Grove put it:

“Writing the report is important; reading it often is not.”

When Ameet Ranadive, a product manager for Twitter, previously worked for the prestigious consulting firm McKinsey & Company, he was struck by the time and care that went into the writing on the slides for client presentations.

More striking, Ranadive wrote, was that some slides never made it into the final presentation. He asked a manager if these slides were wasted work.

The manager “responded with what I would later hear from time to time as a McKinsey maxim: ‘Writing clarifies thinking.’”

Written directions are easier to remember and follow

Now that we have clear thoughts on paper, the author has done their job. But the benefits don’t end here.

Not only is writing a more clear way of expressing information, it’s a better way to comprehend and retain information.

Research analyzing new parents being discharged from hospitals shows that those briefed with both verbal and written instruction on care had a better comprehension of caring for their newborn than those only briefed verbally.

Think about it. If you had to trust a new employee to execute a specific process, would you be more comfortable simply explaining it to them, or knowing they were handed a set of specific, written instructions on the process?

How to write great arguments

Let’s explore three common ways to get your thoughts down on paper in the best way.

Follow the Rule of 3

When Ranadive was at McKinsey, he was schooled in the Rule of 3.

“Whenever you’re trying to persuade a senior person to do something, always present 3 reasons,” he wrote.

Great storytellers and persuaders across generations and disciplines have understood the power of doing things in threes. Movies have three acts, the federal government has three branches, Goldilocks met three bears.

Or as Ranadive put it, “most of us have been hard-wired to expect things in groups of three.”

Not only does the Rule of 3 narrow your list to the three most important points, it forces you to prioritize and order your arguments.

Take a position

A main benefit of writing is the way it forces you to prioritize, to take a clear position on something.

As Ben Horowitz, of the Venture Capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, put it on his blog: great product managers take strong positions. In writing.

“Good product managers take written positions on important issues (competitive silver bullets, tough architectural choices, tough product decisions, markets to attack or yield). Bad product managers voice their opinion verbally and lament that the “powers that be” won’t let it happen.”

Be brief

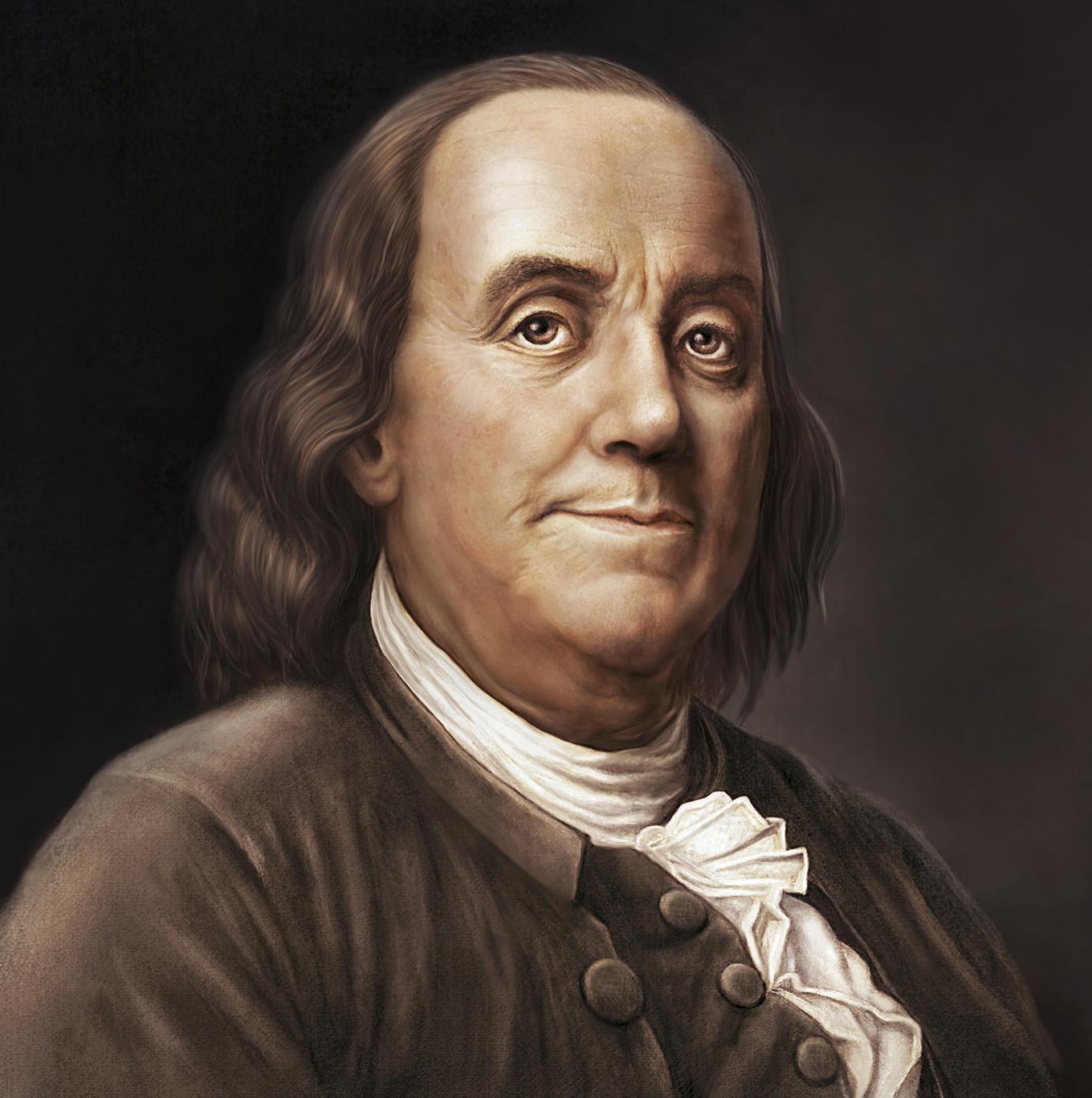

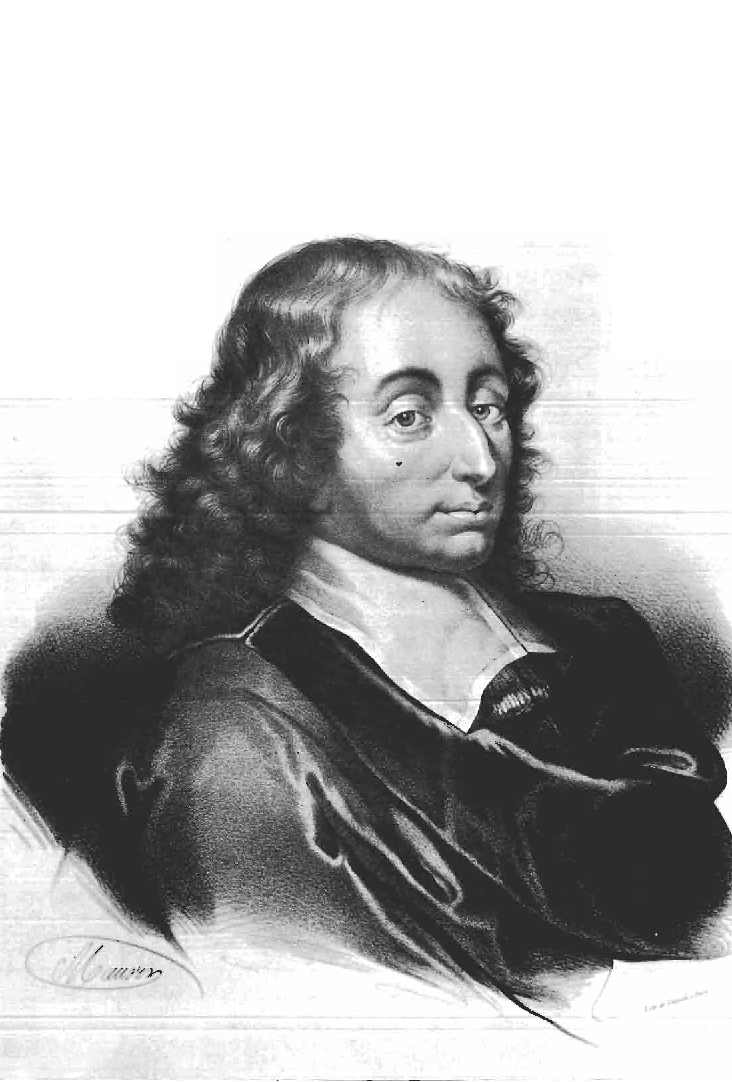

“I would have written a shorter letter, but I did not have the time.”

This quote from French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal holds true today. Getting your thoughts into fewer words is often more difficult than writing on and on. It’s tempting to drone on when writing.

Ian McAllister, Director for AmazonSmile program at Amazon, believes writing concisely is a skill of the top 1 percent of product mangers.

“They should understand that each additional word they write dilutes the value of the previous ones,” McAllister wrote on Quora.

It’s great advice. It you want to communicate effectively, avoid conflict and make a strong argument, you’re going to have to know how to write.

As long as you know when to stop.