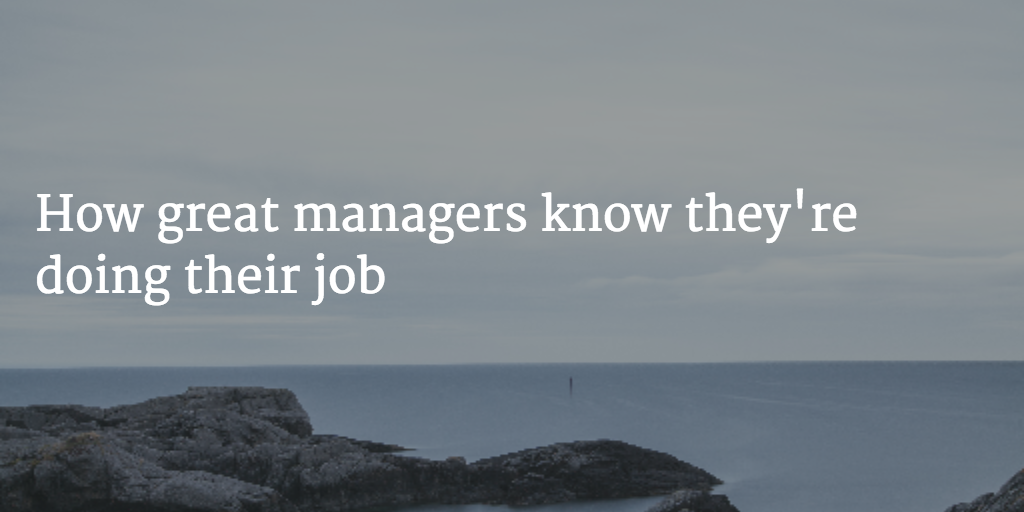

There’s a piece of conventional wisdom in business: People aren’t raw materials. You can’t manage people like they’re widgets on a conveyor belt. People are fluid, emotional, volatile, unpredictable beings that need to be treated as such. You can’t manage people like an assembly line, right?

Maybe not.

The problem with that type of thinking isn’t that people actually are static and predictable. The problem is thinking that a manufacturing process is static and predictable. On a production line, unexpected problems and changes happen all the time. Raw materials arrive flawed, blizzards slow down deliveries, equipment breaks down, orders slow down and inventory piles up, some obscure agricultural disease in another continent wipes out a crop used in a chemical essential to the production process.

Unpredictable, fluid, ever-changing. Kind of like humans, right?

Great managers of people realize this. Great managers of people, in fact, embrace this and approach their job seeking the same consistency and measurable results as a production line operator. They know that their job is measured in the output of the people and departments they’re managing.

It’s the kind of thinking that helped propel Intel into the company it is today, with more than $55 billion in annual sales. It’s a central theme to Andrew S. Grove’s classic 1983 management book “High Output Management.”

The output of the manager is the output of their organization, Grove writes.

“In principle, every hour of your day should be spent increasing the output or the value of the output of the people whom you’re responsible for.”

In other words, a manager is doing their job when their department — when their people — are producing results. A manager at a candy cane factory can measure their personal productivity by the amount and quality of candy canes sent out the door. A software company manager can measure their achievements by the software shipped from the engineers.

Born in Hungary and trained as a chemical engineer, Grove joined Intel at its founding and oversaw much of the company’s massive growth. He became Intel’s president in 1979 and its CEO in 1987.

According to ““High Output Management,” three central models have helped Intel’s managers and can help managers everywhere: applying the methods of production, utilizing managerial leverage and summoning an athlete’s desire for peak performance.

Manage people like a production line

As Grove puts it, anything from managing waiters serving breakfast to recruiting college graduates to a tech corporation can be made more efficient and productive by using strategies honed on the production line.

For example, it’s important to know how value changes throughout the production process.

Intervene at the lowest value stage

Material on a production line becomes more valuable as it moves through the production process, Grove writes. This is true for materials on a production line as well as people on a manager’s team. An egg fried and on the plate is more valuable to a restaurant than one raw in the crate. A college graduate at company orientation after being hired is more valuable than one at an on-campus job fair.

Therefore, if intervention is necessary, it’s best done at the lowest value stage possible, Grove writes. Discard the rotten eggs when they’re raw, not sitting next to toast on a plate.

“Likewise, if we can decide that we don’t want a college candidate at the time of the campus interview rather than during the course of a plant visit, we save the cost of the trip and the time of both the candidate and the interviewers,” Grove writes.

Utilize indicators to measure progress

Another key management principle Intel borrowed from the production line was the use of indicators to measure progress.

“The first rule is that a measurement — any measurement — is better than none. But a genuinely effective indicator will cover the output of the work and not simply the activity involved. Obviously, you measure a salesman by the orders he gets (output), not by the calls he makes (activity),” Grove writes.

Intel, for example, used charts to forecast output over the next several months and compare results to projections. Knowing how results compared to projections help create more precise projections in the future.

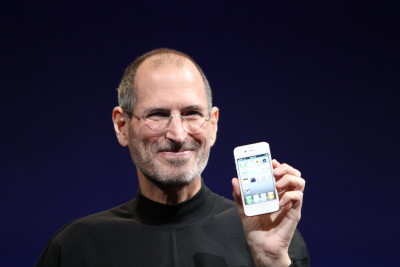

How Apple stays focused on results

Apple has built on much of the processes laid out by Grove. Apple managers, for example, are rewarded only when a product or service is delivered and the company sees results, according to a case study from ERE Media.

For all the fanfare Apple puts into celebrating its product releases, they’re careful to save the celebrations until something is actually delivered.

“The rewards and recognition programs at Apple don’t include a component for effort or trying — only final results. Rather than celebrating numerous product milestones, only the final product unveiling is worthy of a major celebration,” according to ERE.

“The rewards and recognition programs at Apple don’t include a component for effort or trying — only final results. Rather than celebrating numerous product milestones, only the final product unveiling is worthy of a major celebration,” according to ERE.

In other words, you don’t get points for trying.

Utilize managerial leverage to stop wasting time

Learning the difference between high leverage and low leverage activities as a manager can pay huge dividends down the road.

High leverage activities yield bigger results with a simpler effort. A well-executed two minute pep talk to a room of 50 people — one that inspires them all to give their best effort for the next six weeks — is very high leverage. Meddling in the minutia of each of those employees’ progress, individually, for six weeks is a very low leverage activity.

Utilizing leverage is a key way to increase managerial productivity, Grove writes, and can be accomplished in three basic ways:

- When many people are affected by one manager.

- When a person’s activity or behavior over a long period of time is affected by a manager’s brief, well-focused set of words or actions.

- When a large group’s work is affected by an individual supplying a unique, key piece of knowledge or information.

Interruptions: The king of low leverage activities

Dealing with interruptions — putting out fires — is a low leverage behavior that eats up many managers’ days, Grove writes. Interruption responses often amount to solving one problem for one person, rather than instituting policies that ensure the problem doesn’t arise in the first place. And interruptions take away time that could otherwise be spent on high leverage work.

Grove suggests hanging a sign on an office door: “I am doing individual work. Please don’t interrupt me unless it really can’t wait until 2:00.” Afterward, hold an open office hour and batch (another high leverage technique) the interruptions into one session.

How one entrepreneur fights interruptions

The ongoing distractions and digital notifications were a productivity drain for one entrepreneur, Matthew Bellows. Bellows is founder and CEO of Yesware, an e-mail productivity service for salespeople.

“I counted recently,” Bellows told Entrepreneur. “I have 22 inboxes, from e-mail to LinkedIn. The idea that I’m supposed to monitor and troll through these is absurd. I get hundreds of e-mails a day.”

Rather than respond to each individual distraction when it comes up — a very low leverage activity — Bellows instituted a high leverage process. Bellows blocks out uninterrupted time in his calendar to think and checks email only in a few designated times per day.

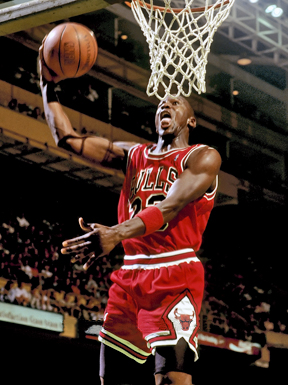

Summon an athlete’s desire

Ask any good pro sports coach what his job is and you won’t get a long-winded answer. You’ll get a quick, specific answer.

“Win games,” most will say.

The really great coaches: “Win championships.”

There’s a lot that goes into being the coach. You’re communicating with staff, planning practices, overseeing team travel and workout sessions, watching film, recruiting talent. All these activities, and great coaches don’t mention them. They consider their job, their one true objective, to be the one thing the coach doesn’t even actually do. The coach doesn’t shoot the basket that wins the big game. The coach never touches the ball.

But great coaches understand Grove’s technique. “My job? Have my team produce results.”

So like a great coach, a great manager gets peak performance from his team.

“The single most important task of a manager is to elicit peak performance from his subordinates,” Grove writes.

Grove suggests making the workplace more like a playing field, injecting it with some of the characteristics of competitive sports. Intel, for example took a mediocre performing field, facilities maintenance, and created a scoring system, with different buildings competing against one another. There was no other prize — no bonuses or incentive to win, just the thrill of being in first place. It worked. Progress in every building picked up and it became a major source of motivation.

Why one CEO likes to hire athletes

One CEO found that competitive spirit was so valuable, he took a liking to hiring actual athletes.

“I like to hire athletes. If you walk through the office of my company, Invoca, you’ll see a semi-pro tennis player, a former sprinter on the UCLA water polo team and a member of the US ski team,” wrote Jason Spievak, CEO and Co-Founder of Invoca. “You certainly don’t have to be an athlete to succeed in business. But I believe that athletes are self-motivated, want to win and know how to help one another achieve a common goal.”

The sales training firm FantasySalesTeam helps companies run sales contests. After studing 164 competitions they helped run, the company crunched the data and came up with a set of tips for inter-office contests.

Among them: Update results frequently, make the results very visible, and team-based competitions are more effective than individual competitions.

Approach employee relations this way and performance will skyrocket. As Grove puts it, soon colleagues and employees will feel less like workers, and more like high performance athletes.

“Turning the workplace into a playing field can turn your subordinates into ‘athletes’ dedicated to performing at the limit of their capabilities — the key to making our team consistent winners.”

P.S. If you liked this article, you should subscribe to our newsletter. We’ll email you a daily blog post with actionable and unconventional advice on how to work better.