So you want to build a billion-dollar company, and it’s because you want to make people’s lives better by solving a problem while hitting it big, rich, and famous. Sounds like a winning combo of incentives to drive you to achieve startup success.

It’s not like both motives can’t coexist. Humans, complex beings that we are, walk around with a jumble of intentions, impulses, and aspirations in our heads — instead of one clearcut reason for why we do things.

The thing is, you would think that having multiple motives would result in, well, more motivational power. When you can hit two goals with one activity, don’t you just have more incentive to do the activity? If you want that promotion because you get to expand your skillset and increase your prestige, doesn’t that help drive you even harder to go for it?

There’s one problem. There’s a tricky truth about motivation that might be preventing your best performance.

Getting Outstanding Performance Backwards

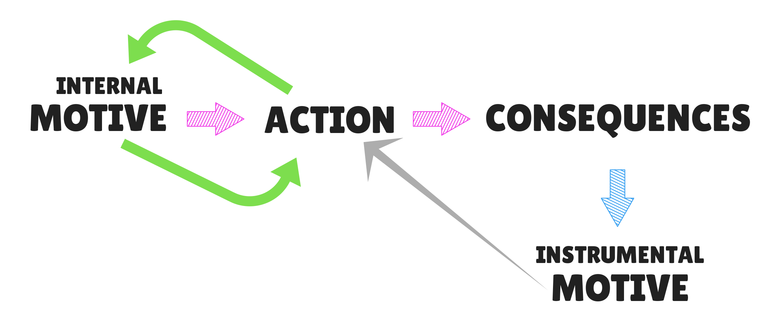

It all comes down to how two kinds of motivations, called internal and instrumental motives, interact rather than merely coexist.

Internal motivation link goals with activities, while instrumental motives don’t. For example, aiming to build a Facebook or an Apple because you’re driven by fortune and fame is an instrumental motive since the reason and venture aren’t inherently connected. There are plenty of other ways to get rich and famous without building a startup. On the other hand, if your motive is to solve a problem or create something great, that’s internal. You’re pursuing something for the sake of the activity itself.

When psychologists Amy Wrzesniewski and Barry Schwartz studied the trajectories of over 11,000 West Point cadets, they discovered how we misunderstand the role multiple motives play in success. The cadets, upon entering the military academy, rated 31 motives for why they decided to enroll — which included internal motivations (the desire to become an Army officer and for self-improvement through leadership training) and instrumental motives (improving job prospects and earning potential) among others. The researchers then tracked the cadets’ paths over years.

Stronger internal motivations predicted superior performance — greater likelihood to receive early promotions, graduate, become commissioned officers, and to even extend their service beyond the mandatory five-year term. And that wasn’t the interesting finding. There’s been plenty of evidence that intrinsic motivation provides more powerful drive.

The unexpected discovery was that when cadets held both internal and instrumental motives, performance went downhill on every account. “They were less likely to graduate, less outstanding as military officers and less committed to staying in the military,” the study authors summarize. It didn’t matter if the internal motivations were strongly held. Instead of both kinds of motives reinforcing each other to add an extra edge, they competed against each other.

Why are those instrumental motives so tempting to pursue? We mix ourselves up by basing our motives on positive instrumental consequences. We basically get it backwards:

Just because a book can get a good review in The New York Times doesn’t make that instrumental consequence a great motive for writing. But it’s really easy to get caught up on such benefits and rewards because they sound so persuasive and beneficial. Doesn’t it seem irrational to argue against getting extra cash as a bonus or achieving good grades or making a smart career decision?

But if an activity isn’t inherent to the goal you’re pursuing — then why do that activity over something else? It’s far less likely that you’ll go above and beyond without that connection.

The Pursuit of Meaning

The takeaway from the study, according to Wrzesniewski and her colleagues, is to focus on purpose and meaning to make that connection between pursuit and what you do:

[S]tructure activities so that instrumental consequences do not become motives. Helping people focus on the meaning and impact of their work, rather than on, say, the financial returns it will bring, may be the best way to improve not only the quality of their work but also — counterintuitive though it may seem — their financial success.

Managers should be especially careful about how tasks are structured and performance incentivized. Increase opportunities for exercising autonomy, gaining mastery, and using strengths. Regular reminders and discussions about how tasks connect with organizational purpose can help maintain the strength of internal motivations, as the larger picture can often fade in the day-to-day. Consider how instrumental incentives like bonuses can actually detract from performance and persistence.

The easy objection to bring up as individuals is the ol’ employee blues — I’m just an insignificant cog, my job is meaningless, nothing I do matters much anyway. Yet you can practice what Wrzesniewski and psychologist Jane Dutton call job-crafting, a continual process in which you’re re-engineering your job by reframing and customizing tasks, relationships, and perceptions to strengthen your internal motivations.

The easy objection to bring up as individuals is the ol’ employee blues — I’m just an insignificant cog, my job is meaningless, nothing I do matters much anyway. Yet you can practice what Wrzesniewski and psychologist Jane Dutton call job-crafting, a continual process in which you’re re-engineering your job by reframing and customizing tasks, relationships, and perceptions to strengthen your internal motivations.

Map out your current tasks and how much time and energy they take. Then, consider how you can rearrange and design a workload by considering your motives, strengths, and passions. How can you rearrange, build on, and edit what you do and how you do them to increase your engagement?

This means way more than just an attitude adjustment. Wrzesniewski found that you can have the same title and job description but in reality be doing different jobs. When she interviewed hospital custodians, those who crafted their jobs felt like they were doing something worthwhile. They spent time with patients who had no visitors, found out which cleaning products would be least irritating, changed room decors. In short, they were being thoughtful on the job, drawing on their skills and relating to a larger purpose like connecting with the patients and the healing role of the hospital.

It all goes back to that magical trio of what really drives us and provides meaning at work: a sense of autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

* * * * *

When it comes to motivation, more is not better, meaning is.

People, looking for meaning, self-expression, and growth, often search outside to volunteer or dream about dream jobs — instead of within. But finding internal motivations doesn’t turn on an organization with an inspirational mission statement or necessarily require you to quit to follow your passion. Meaning, purpose, mastery, and growth — these all turn on how you are doing what you do, the relationship between the means and the end.

Injecting meaning into your job isn’t some kind of luxury, reserved only for dream jobs. It’s just as vital, if not more, to consider meaning and calling when you feel like you’re just in it for the paycheck or that you’re stuck in a never-ending grind.

Liked this post? Subscribe to our free newsletter for more great content on productivity, management, and how to work better!

Photo: Kevin Houle