When Toy Story broke box office records and Pixar was the biggest IPO of 1995, it seemed that company co-founder and president, Ed Catmull, had finally made it. He not only met his twenty-year-long goal of making the first computer graphics movie, he also created a successful company. “As a manager, I felt a troubling lack of purpose. Now what?” he wondered. Would he “merely” run a company? What was special about that?

His outlook changed upon learning he’d been completely oblivious to something that had put Pixar at risk, throwing his beliefs about success into a new light. Managing in a successful company is in fact a demanding, evolving, and rewarding job. The special challenge is to cultivate and maintain conditions, context, and company culture that you can’t always see.

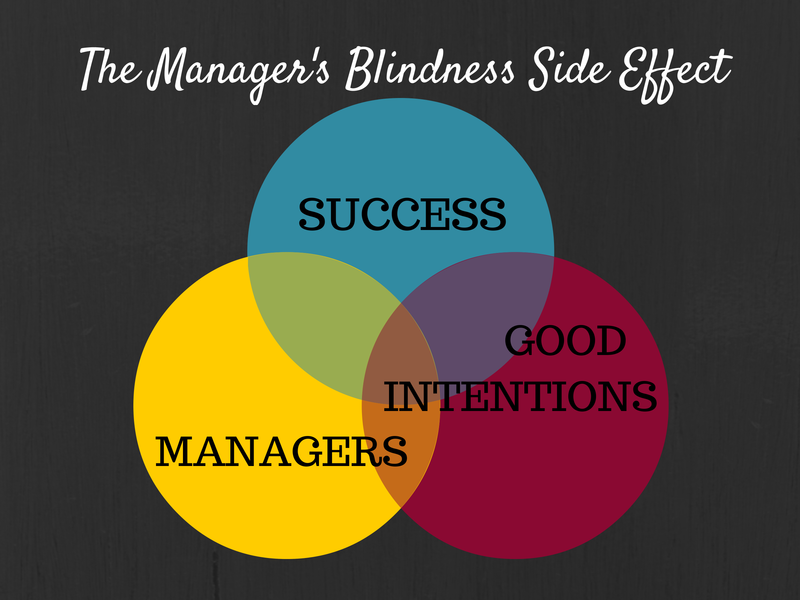

Just because you think you can see how the sausage is made doesn’t mean you really know what’s going on in your team and company. In fact, success and great qualities can even obscure problems, creating a peculiar blindness for diligent managers on their toes. Even when you have what seems like a winning combination of talented leaders, rising fortunes, and good intentions, you can still miss something vital.

How the Sausage Gets Made

When Vienna Beef moved to a shiny new plant, they didn’t expect to lose the very thing that put them on the map.

For over a century, the Chicago-based company has been making their famous all-beef natural casing hot dogs, identifiable by their distinctive snap when you bite into them. When Vienna Beef moved from Chicago’s South Side, where they’d expanded over the course of 70 years, to a shiny new plant on the North Side, they encountered a major problem.

That characteristic snap had disappeared, and the sausages were pink instead of bright red. The company couldn’t figure out where they were going wrong. They had the same recipe, the same ingredients, the same process, not to mention their new, top-of-the-line facilities and equipment. Yet somehow, they didn’t have the works.

For a year and a half, they struggled to get that color and snap back into their hot dog until one day, over a few drinks and reminiscences about the old plant, they remembered a guy called Irving. He was a well-loved employee who hadn’t stayed on because of the new commute, and his job had been to carry uncooked sausages through the jumble of the old plant to the smoke house.

The new plant, however, had no jumbled maze. It was the very model of efficiency. Sausages were made in a cold room and then zipped right over to the smoke house in the next room. It was Irving’s half-hour trip — trekking through vents of hanging pastrami, the boiler room, tanks cooking corn beef, and up an elevator to bring the now-warmer sausages into the smoke house — that was missing.

CEO Jim Bodman told This American Life in 2003, “So we said, oh my god, that is of course the reason. Why didn’t we know that? That’s the dumbest thing in the world to not realize it’s right there.” Vienna Beef ended up building a room to simulate the conditions of Irving’s trip, where the sausages can warm up before they’re cooked.

You can get everything right, have all the best tools and people, even make it big — and still not understand all the factors that bind and flow through a company, putting the very culture, product, and employees that make it distinctive and wonderful at risk. The leaders at Vienna Beef probably thought they were making a logical, hard-earned move up in the world, upgrading from a factory that first sent deliveries by horse-drawn carriage. They thought they held the recipe for success but it turns out they were blind to one key ingredient.

Paying Attention Isn’t Enough

To make Toy Story come to fruition, Catmull knew he had to manage Pixar’s dynamics well. Specifically, “I was determined that Pixar not make the same mistakes I’d watched other Silicon Valley companies make.” So he was extremely deliberate about being open and accessible, aiming to see every problem and hear out all his employees.

However, he found out that the company’s production managers ended up feeling disrespected and trivialized, “like second-class citizens” — so much so that they were hesitant to stay on even after Toy Story’s amazing success. Catmull recalls in his memoir:

My total ignorance of this dynamic caught me by surprise. My door had always been open! I’d assumed that that would guarantee me a place in the loop, at least when it came to major sources of tension like this. Not a single production manager had dropped by to express frustration or make a suggestion in the five years we worked on Toy Story.

What Catmull pieced together was that product managers, responsible for keeping projects on time and resources on budget, were usually the people saying “no” and thus seen by creative and technical employees as obstructive micromanagers. The production managers didn’t speak up for two noise-canceling reasons: since their jobs were typically freelance gigs, complaining was considered risky and meanwhile they strongly believed in the mission of Pixar’s project. So they put up and shut up.

Catmull was blind to how key people were working together, taken in by the fact that Pixar’s purpose was so compelling that it masked the production managers’ pains while it drove their very efforts. “I had completely missed something that was threatening to undo us. And I’d missed it even though I thought I’d been paying attention,” he confesses. He spent these five years by being the very model of a self-aware, supportive, approachable manager but open doors, good intentions, and self-awareness still weren’t enough to give him insight into points that mattered.

And that’s the scary, challenging, formidable thing about great leadership and management. “Being on the lookout for problems … was not the same as seeing problems,” as Catmull concludes. Even the best leaders in the midst of successes and wins can be blind to something crucial.

* * * * *

The people, processes, and environment in a company make up a complex ecosystem of mixed motivations and management dynamics that are inherently difficult to untangle and understand. And it’s this snarling challenge that filled Ed Catmull with a new sense of purpose back in 1995, to keep at building a vigorous company that would carry on from one generation to the next by “foster[ing] a culture that would seek to keep our sightlines clear, even as we accepted that we were often trying to engage with and fix what we could not see.”

When you think you have an intimate knowledge of how things work — all the metrics and mentorship and bullet-pointed business wisdom and entrepreneurial realtalk — even when you think you’re adapting like a fox, chasing increased efficiency, and winning like a boss — you might actually be totally blind to what’s giving or extracting breath from the lifeblood in the first place.