Here’s the thing about bosses who micromanage. None of them think they’re actually doing it.

It’s easy to see how this happens. Managers, typically, were once experts at the work their subordinates are doing. That’s likely why they were promoted.

But this changes at the management level. Their jobs are more strategic, less hands on. Many managers aren’t up for the transition, so they sink back into what they’re familiar with — the gritty details of the work they used to do.

As author Ron Ashkenas, a managing partner of Schaffer Consulting, put it in Harvard Business Review:

“However, at higher levels managers usually need to dial down their operational focus and learn how to be more strategic. To do so, managers have to trust their people to manage day-to-day operations and coach them as needed, rather than trying to do it for them.”

So managers gravitate toward the familiar. They think they’re being helpful. And they micromanage. And many employees just put up with it. Cost of doing business, they figure. Something to complain about at the bar. Even worse, many executives see that the managers below them are micromanaging their staff, and they do nothing to stop it. Oh well, they say. Cost of doing business, right?

Not right. Actually incredibly wrong. Micromanaging isn’t a minor quirk or annoyance. It’s nothing to take lightly. It’s a poisonous behavior that creates a vicious cycle of despair. It can sink a whole department, even a whole company.

Micromanaging a vicious cycle of despair

Harvard Business School professor Teresa Amabile and psychologist Steven Kramer asked hundreds of employees across various companies to maintain a daily diary recording their highs and lows during the work day. The pair eventually analyzed more than 12,000 diary entries and recorded the findings in their book “The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work.”

What they found wasn’t just that micromanaging was a short-term annoyance or a necessary evil. The practice “stifles creativity and productivity in the long run,” they wrote.

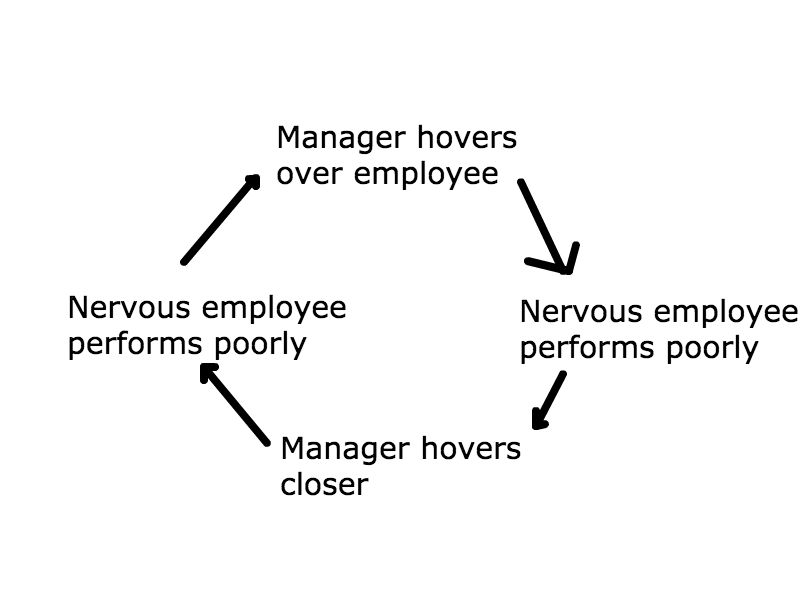

A vicious cycle kicks in. Micromanagers summon fear and unhappiness, that leads to worse work from the employees, which leads to more harsh intervention from the manager, which leads to even worse work. Around and around it goes.

From the authors:

“When people lack the autonomy, information, and expert help they need to make progress, their thoughts, feelings, and drives take a downward turn — resulting in pedestrian ideas and lackluster output. Managers panic when they see performance lagging, which leads them to hover over subordinates’ shoulders even more intrusively and criticize them even more harshly — which engenders even worse inner work life.”

Autonomy, on the other hand, fosters hard work.

Research from University of Pennsylvania professor Alexandra Michel found that employees work more, harder and better when given autonomy over their work schedules. Michel spent 12 years studying young executives at two large investment banks to try to understand why so many educated young people burn out in the profession by age 35.

The bankers felt more motivated when bosses gave them autonomy over their schedule. This is shown in one conversation from the research:

Bank B associate: “I could not work for an organization that required me to come at 9 a.m. and leave at 5 p.m. I want to be in control of my schedule.”

Researcher: “But you work a lot longer than 40-hour weeks.”

Banker: “Yes, but this is my choice. I decide when the work gets done.”

The four ways to become a soul-crushing micromanager

After analyzing thousands of complaints and insights from employees and managers, Amabile and Kramer identified four key mistakes micromanagers make.

Here are the mistakes, and ways you can avoid them.

1. They fail to allow autonomy in carrying out the work.

As we’ve shown, people work best when they feel some freedom over how and when they do the work. You may not be able to blow the doors off the schedule entirely, but it’s possible to interject a little more freedom. One manager documented in “The Progress Principle” overcame this by setting a clear strategic goal for his team, but imposed no requirements on how the team meet that goal. The team, therefore, was motivated by a goal and not by manager-imposed rules.

2. They frequently ask subordinates about their work without providing any real help when problems arise.

These bosses are always checking in to see what their employees are doing. At iDoneThis, we build a tool to let everyone on your team see what you accomplished each day. On our team, there is no micromanaging because we’re transparent about what we’re working on each day. Micromanaging would be redundant. If my boss wonders what I’m working on, he can look on iDoneThis and see what I’m up to in a way that doesn’t interrupt my workflow or throw me off my game.

3. They’re quick to affix personal blame, rather than guiding an open exploration of causes and possible solutions.

Micromanagers have no problem pointing the finger when something goes wrong. This makes employees afraid of bringing up potential problems early, when they could actually use some intervention. People keep problems hidden from their managers, hoping they’ll be solved without getting the manager involved. Maybe this works sometimes. But when it doesn’t, you’ve got a problem that’s lingered long enough to grow into a full-blown crisis.

4. They rarely share information with team members about their own work.

Ever notice how the bosses doing the most nitpicking on other people’s work are the ones least likely to share what they’re actually working on? What’s the boss even do? If it’s a question people have to ask, there’s a chance it’s a question the boss doesn’t have a good answer for. Avoid this by being transparent about your own work, too (see step 2).

As you can see, micromanaging isn’t a necessary evil or an effective management style. It’s a seriously flawed method of operating that will poison your team and all their hard work. But by providing autonomy and fostering transparency, micromanaging can be a thing of the past. You can get back to the important stuff.

Now what was it that you were working on today?

P.S. If you liked this article, you should subscribe to our newsletter. We’ll email you a daily blog post with actionable and unconventional advice on how to work better.