At the design firm IDEO, you have to be cooperative or you won’t survive.

Engineer and designer Jimmy Chion, for example, spent his first few months at IDEO going from designing “futuristic interactions inside a car to working at a handbag manufacturer to make a purse for London Fashion Week.”

Who you work with changes all the time as well. While teams generally exist for a few months, you could be together for as little as two weeks or as long as a year, depending on the project. To add to the flux, as Jimmy told me, “every team basically starts from scratch every single time,” collectively deciding what tools and processes to use.

Creativity is a quality mostly equated with individuality. Yet IDEO has to constantly corral extremely creative people into shifting configurations to deal with different clients and projects. “Everyone here is really versatile in the way they work. You have to be — you’re not on any same project twice,” explains Jimmy. Everyone at IDEO can work with everybody else at IDEO, which is the cool part.”

Understandably, that means they’re not looking for lone creative geniuses at IDEO. Instead, what one of the most creative companies in the world hires for is the ability to collaborate.

Screening for Social Creativity

Tim Brown, IDEO’s CEO, makes it a point to look past the portfolio to figure out how people work and whether they are versatile and collaborative enough to make it. He has one simple method of testing job candidates for their ability to work with others.

He looks for people who say “we” more than “I” when talking about what they’ve done. Using this language of the collective rather than the individual provides one glimpse into someone’s inclination for teamwork. “If they’re generous with giving others credit,” writes Brown, “I know they’re team players and will accept feedback.”

The “we” test is not something that only exists as a filtering mechanism. It’s a guiding principle of how IDEO gets stuff done. In the company culture book, The Little Book of IDEO, they explicitly state: “Our most powerful asset in the arsenal, by far – the word ‘we.’”

When a whole business is built around constantly adapting, learning, and working with different people and new perspectives, you need team players who will gladly help and support each other “through the complex emotional minefield of our client projects.” This is an environment where striking out on your own like the solitary rockstars and ninjas that many in the tech world boast about is explicitly counterproductive.

Debunking the Myth of the Lone Genius

The idea of the lone creative genius is tenacious, for its romance and glamour, or maybe simply because it’s easy to idolize and admire one person instead of a team.

An intriguing study by sociologist Katherine Giuffre looking at some of the most famously “loneliest of recluses” — writers Emily Dickinson and Charlotte Brontë and painter Paul Gauguin — puts that lone genius idea to rest. She compared their levels of network density — measured mostly by correspondence — to their periods of productivity.

Dickinson, Brontë, and Gauguin weren’t toiling away by themselves when creating their best work. They were communicating and collaborating with others, receiving and soliciting feedback and support. For these most creative periods, Dickinson and Gauguin carried out a rich correspondence, writing about their work, receiving feedback, and discussing theories, while Brontë in living together with her literary sisters “wrote their books in close collaboration.”

The artists weren’t the most creative when they were alone and isolated but when their social network density was higher (but not so dense as to be stifling).

Building Social Networks of Helping

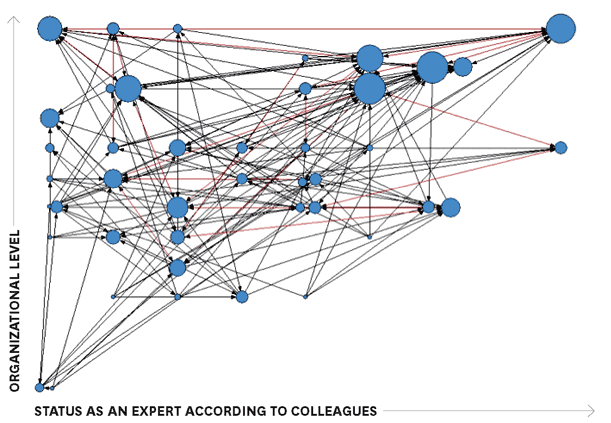

Interestingly, when Teresa Amabile, Colin Fisher, and Julianna Pillemer mapped out all the helping networks at IDEO, they discovered that the company had created a dense internal network of collaboration and support.

This looks different from the helping networks in most other organizations, which are made up of cliques or hub-and-spoke patterns that center around a few central characters. At IDEO, the helping network was broad and dense. Everyone supports each other in the spirit of “we”. The authors note that in the particular office they studied, “nearly every person was named as a helper by at least one other person.”

In Giuffre’s study, she explains that there are multiple conceptions of creativity — “as an attribute, as an action, and as an outcome.” We often get caught up with creativity as a personal attribute more than we do as an outcome, but in doing so, lose sight of an integral dimension of building great teams and organizations. Creativity doesn’t just result from putting a bunch of inventive people in a room or adding an artsy personality to a team. It happens from people working together.

P.S. If you liked this article, you should subscribe to our newsletter. We’ll email you a daily blog post with actionable and unconventional advice on how to work better.