The Practical Guide to Company Culture for Startups

Company culture can be an enigmatic idea to a first-time startup founder, but it’s an absolutely vital resource that can buoy your company in tough times, that’s like jet fuel when times are good, and that can mean the difference between survival and giving up.

In this guide, we want to make company culture a concrete concept to you that you can make real in your company today. We use practical examples from leading companies and entrepreneurs that are on the bleeding edge of innovating company culture into a competitive advantage.

Let us know on Twitter at @idonethis what you think about this guide and share with us how your company is developing and cultivating its culture.

Table of Contents

- How to Figure Out Your Company Culture

- Real Company Culture Comes from the Bottom Up, Not from the Top Down

- Where the Rubber Meets The Road: Living Your Values

- Build Company Culture through Hiring and Firing

- Find Your Company’s Voice for Internal and External Communication

- How to Evolve Your Company Culture Over Time

1. How to Figure Out Your Company Culture

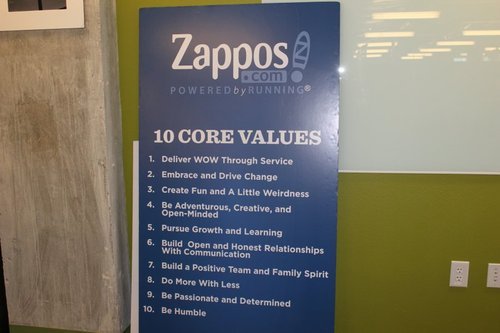

Successful entrepreneurs like Tony Hsieh, CEO of Zappos, exhort startups to write down their core values on Day 1 and make company culture a first-order concern from the very beginning.

Have you tried it? The problem is that after you look at what you wrote, you’ll probably see a bunch of boring clichés. Many of your company values might sound suspiciously similar to Zappos’s and Netflix’s. Your company couldn’t sound less exciting.

It seems like it should be easy, but figuring out your company culture is actually really tough. But rest assured that the effort is well worth it—defining and evolving your company culture is one of the most important parts of a founder and executive’s job.

It’s not a single moment where the culture is defined, either. It’s a continual process, but it has to be an intentional one. Here’s how to figure out your company culture and make it real.

1.1. What Will Fast Company Write about Your Startup’s Company Culture?

Molly Graham, former Head of Mobile at Facebook, who worked with Mark Zuckerberg to define Facebook’s company culture in 2008, recognized the common pitfall that most company cultures are super boring. She came up with an ingenious solution to the problem, rooted in a simple trick that Amazon uses to build its products, that helped Facebook own the Hacker brand that defined the company through its IPO.

How Amazon Ensures Products that Excite Customers

At Amazon, before the product has been built or even spec’d, the product manager has a vital task that will shape the entire product development process. The product manager must write a press release that announces the finished product.

They “are centered around the customer problem, how current solutions (internal or external) fail, and how the new product will blow away existing solutions.” Written from the customer perspective, they’re short — just a few of paragraphs long.

What makes the press releases so powerful is that the product manager is forced to distill to the essence why customers will get excited about the new product: “the product manager should keep iterating on the press release until they’ve come up with [customer] benefits that actually sound like benefits.”

As Ian McAllister, General Manager at Amazon puts it, “If the benefits listed don’t sound very interesting or exciting to customers, then perhaps they’re not (and shouldn’t be built).”

Your Startup Culture Press Release

When you’re trying to define your company culture, you have a bunch of adjectives and phrases that describe you and your company. What Graham realized at Facebook was that you need to turn those adjectives into a story that leaves the boring bits out and cuts to the heart of why the company is different and compelling.

For Amazon, the pre-product press release is the story that answers the fundamental question of why the product is interesting to customers. Graham had an insight — why not apply the same idea to company culture? Her solution was powerful but simple: put down on paper what you want Fast Company to write about your company culture in two years.

Like the Amazon press release, if it’s boring, do another draft. Keep going until you have something that your customers (current and potential), your employees, and your supporters recognize as unique and distinctive. Graham goes as far as to say “you should only write down your story if you are willing to stick your neck out and make it controversial.” Why? Because company culture should not only sound appealing to the people you want, it should also sound unappealing to the people you don’t want.

If you’re not willing to take a stand with your company culture, you shouldn’t bother. It’ll be dull and antiseptic, unable to guide decision-making on tough questions, and no one will care.

* * * * *

Amazon calls its philosophy “working backwards” and at its core, it’s about “driv[ing] simplicity through a continuous, explicit customer focus,” describes CTO Werner Vogels. “[Y]ou start with your customer and work your way backwards until you get to the minimum set of … requirements to satisfy what you try to achieve.”

The press release bridges that critical perspective gap between inside and outside, nailing “how the world will see the product — not just how we think about it internally.” Do you want Fast Company to write two years down the line about how your company’s amazing customer service starts and ends with its company culture around delivering WOW (Zappos)? Or do you want it to write about the Hacker Way, your philosophy on breaking rules to make rapid progress (Facebook)?

Start at the end. Think about that compelling, specific, and controversial company story that you want Fast Company to tell, and work backwards to figure out your company values and what you need to do to get there.

1.2. Case Study: A Remarkable, 10-Year-Old Email from Tony Hsieh on Zappos Company Culture

In early 2005, Tony Hsieh was a relative unknown.

Zappos was a fast-growing company, but it was far from being the household brand that it is today. While it hadn’t yet come up with its core values for which it is famous today, the company had a growing sense of its own company culture and identity. They were on the cusp of something big.

It was against this backdrop that Hsieh emailed this update to investors, employees, partners, and friends of Zappos. It’s an awesome behind-the-scenes look at what drove Hsieh and kept him up at night. In this glimpse into how Hsieh thought about building a company, you can see the seeds of what would grow into Zappos’s world-famous company culture and brand.

Within five years, Zappos would hit $1 billion in revenue and Hsieh would author Delivering Happiness, a #1 New York Times Bestseller, which would catapult him into being one of the most influential business persons in the world. But here is an unfiltered look into the mind of Tony Hsieh, before the notoriety and fame.

From: Tony Hsieh

Date: Tue, Feb 1, 2005 at 3:19 PM

Subject: Zappos.com Update – February 1, 2005

Dear Investors, Employees, Partners, and Friends of Zappos:

With the WSA show right around the corner, I thought it would be a good time to send out another company update.

We had a busy and hectic holiday season, and we’re happy to announce that we surpassed our goal of $175 mm for 2004 by ending the year with $184 mm in total gross merchandise sales! For 2005, our goal is to break the $300 mm mark.

For those who don’t know, here are our historical sales numbers:

1999: Almost nothing

2000: $ 1.6 mm

2001: $ 8.6 mm

2002: $ 32 mm

2003: $ 70 mm

2004: $184 mm

2005: $300 mm (goal)

With January already behind us, we are on track to beat our 2005 goal. We finished January at $28 mm compared to our internal plan of $22.5 mm. (In fact, we’ve temporarily cut back on some of our marketing efforts in order to slow down our sales while we staff up our Customer Loyalty Team.)

Last year was an eventful and exciting year for us. Here are some of the highlights from 2004:

- We moved our corporate offices from San Francisco to Las Vegas, with the majority of San Francisco employees relocating with the company.

- We increased our line of credit with Wells Fargo to $40 mm.

- We secured $20 mm in equity financing from Sequoia Capital, the same venture capital company that funded Yahoo, Google, and Paypal.

- We were ranked #15 in Inc. Magazine’s annual list of the 500 fastest-growing private companies in the United States.

- We expanded our warehouse from 120,000 square feet to 280,000 square feet, capable of holding 3 million pairs of shoes.

- We grew our total workforce to 500 people (200 in Las Vegas, 300 in Kentucky).

- We expanded our Customer Loyalty Team hours to 24/7, 365 days a year.

- We added handbags as a new category to our web site.

- Within shoes, we added many additional categories, including kids’, outdoor performance, skate, running, western, and couture.

- We increased the number of brands offered on our web site to over 400.

From a merchandising point of view, last year our focus was on expansion. This year, our focus in merchandising will be on the growth of our existing businesses and the development of our people.

We have added an Inventory Analyst to help us keep a closer eye on our inventory planning and execution, and make us more efficient and profitable.

We have implemented a rigid training program for our merchandising team so that we can develop the best merchants in the industry. We believe that merchandising is both an art and a science, and we want to make sure our merchandisers embody this philosophy.

We have also made the extranet more robust in order to strengthen our partnerships with our vendors and create win/win relationships for each of our businesses.

On the marketing front, we will continue to focus advertising on our service and selection, rather than on price. We will be looking to integrate our advertising efforts more with those of our vendor partners.

Our initial tests in 2004 with print advertising were very promising, and for 2005 we plan on increasing both our print advertising budget as well as our online advertising budget. But from a marketing perspective, what’s most exciting to us is that the biggest drivers of our growth are repeat customers and word of mouth.

The word of mouth effect has quietly snowballed over time, and we see our long term plan of building a service brand slowly coming into place. Internally, we have a saying:

“We are a service company that happens to sell shoes.” (And now handbags.)

From a sales perspective, our goal is to get to $1 billion a year in gross merchandise sales by 2010 (or possibly sooner), which is why at this stage of the company we have decided to reinvest most of our profits back into our growth. Rather than maximizing short-term profits, we’re taking a long-term view and focusing on building the business for the long haul. We’ve grown quickly over the past 5 years, but we are just scratching the surface of what’s possible.

But it’s not the numbers that are the most exciting… It’s the opportunity to build a company culture and consumer brand that is centered around the service, not the shoes or the handbags.

We are often told that customer service is sorely lacking throughout most of this country. If we constantly focus on improving the customer experience and cause people to think about service everytime they think about Zappos, then in the long term, we believe that we will succeed as a company.

However, our service can’t just be “good enough”… We need to go above and beyond people’s expectations. Internally, we call this our WOW philosophy. Our neverending goal is for every interaction with every customer to result in the customer saying “WOW” — so that they will shop with us again and tell their friends and families about our service.

However, building a service organization is much easier said than done. It starts with extending the WOW philosophy beyond just our customers. We also need to extend it to our vendors, our employees, and our other business partners. Some people might call this “brand resonance”, but it’s really the only way to build an enduring brand.

With our vendors, we’ve worked hard at building partnerships and avoiding the adversarial relationships typical in retail/wholesale relationships. And we plan to continue to do so in 2005.

Our biggest challenge for 2005 will be managing our growth so that we stay consistent with the Zappos brand and grow our service-focused culture. We are now at the point where, with our rapid growth (more than doubling year over year, every year), we risk losing our service-focused culture if we don’t do a good job of actively managing it.

It’s really the only thing that keeps me up at night… and the only way for us to succeed is to continue to apply the same partnership philosophy that we give to our vendors to our employees as well.

The truth is, this is uncharted territory for us. I’ve never been part of a company that’s grown from nothing to hundreds of millions of dollars in sales. I’ve never been part of a company that’s grown from 5 people to a staff of over 1000, which is where we plan on being by the end of this year.

So undoubtedly, we will make mistakes along the way, and we won’t do everything right the first time. But that’s okay, because that’s also what we want our culture to be about. We’re not afraid of making mistakes, but we’re also quick to turn them into learning experiences and fix the mistakes when they happen. Part of the Zappos culture is having faith that in the end, we will figure things out, and we will grow stronger through the experience. It’s how we got to where we are today.

At the end of 2004, we published our first culture book — a compilation of opinions about what the Zappos culture means to each of our employees. The culture book showed that no one person owns or dictates the Zappos culture. It is a collective effort, and it’s exciting to be part of a company that has accomplished so much by sheer willpower. The drive to succeed is inherent in our culture.

The Zappos brand will live and die by the service that we deliver. So the question — to everyone receiving this email — is this: what can we do better to WOW you, whether you’re a customer, an employee, a vendor, or a business partner? Only with your feedback can we improve, and build something that has never existed before: a well-known brand, accessible to everyone, that promises nothing less than a WOW experience.

If we can accomplish that, then we will have built a company culture and brand that we can all be proud of. That’s why in order for us to succeed, the Zappos brand needs to be about the service, not about the shoes.

We have a long road ahead of us, but it’s an exciting one. Thanks to everyone for your support through 2004, and we look forward to an even better 2005!

Tony Hsieh

CEO – Zappos.com

1.3. Case Study: This Deli Makes $50 Million a Year By Staying Small

It’s crazy to learn about a deli that makes $50 million dollars a year. It’s stranger yet how they’ve done it.

Most restaurants grow their revenue by opening more locations and eventually developing a franchise model like Subway. You sell more and more sandwiches as you open more and more stores. The problem is that the quality inevitably declines. Your restaurant becomes more about volume than great food and remarkable service.

Zingerman’s, a deli based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, faced this fork in the road: open more locations or face continually stagnating revenue growth. Instead of choosing the conventional franchise path, they blazed their own trail.

They grew from $5 million to $50 million in annual revenue in a way that allowed them to stay small and preserve the things about the company that made them special. But it wasn’t in food or service where they innovated to drive 10x revenue growth but in an unexpected way — by innovating on organizational structure and company culture.

Keeping It Zingy — Zingerman’s Community of Businesses

From the very beginning, Zingerman’s founders Paul Saginaw and Ari Weinzweig had set out to do something totally original and “build an extraordinary organization.”

But rather than focus on profits like everyone else, they wanted their company to have a different organizing principle — one “where decisions would not be based on who had the most authority but on whoever had the most relevant information.” This would allow “everyone to help run the business” and each employee to feel “personally responsible for its success.”

So in 1994, with the deli producing $5 million in annual revenue, the founders sat down and wrote their vision statement for what they called “Zingerman’s Community of Businesses,” a loosely organized group of local businesses under the Zingerman’s umbrella that gave its employees an opportunity to become partners.

Each ZCoB business would be founded and operated by a Zingerman’s employee-turned managing partner who had gone through extensive in-house training on Zingerman’s company culture, values, and how it does business. Both the managing partner and Zingerman’s would contribute capital to get the business going. The result is a bunch of small startups based on the Zingerman’s company culture and brand, all based locally in Ann Arbor.

Like the startup world, some ZCoB businesses have failed while others have succeeded. Today, ZCoB spans nine businesses along with “650 employees, 18 managing partners and combined annual sales of $50 million” of which the Deli only accounts for $14 million.

Do Well By Doing Good

Business journalist Bo Burlingham calls companies like Zingerman’s “small giants,” which are “companies that choose to be great instead of big.” In tech, it’s companies like 37Signals, Moz, Wistia and Buffer that eschew VC cash in favor of growing slowly so that they can build a company that’s unique and remarkable.

But it’s hard not to focus on making money, because entrepreneurs are besieged by near-constant pressure to expand and grow.

Small giants think differently, sharing seven characteristics:

1) The leaders question the usual definitions of success in business and imagine other possibilities

2) The leaders build the kind of business they want to live in, rather than accommodating themselves to outside forces

3) The companies have an extraordinarily intimate relationship with their locations

4) The companies cultivate exceptionally intimate relationships with customers and suppliers, based on personal contact, 1:1 interaction, and mutual commitment to delivering on promises…

5) The companies have unusually intimate workplaces…

6) The companies may have unique corporate structures and modes of governance

7) The leaders bring passion to whatever the company does. “They had deep emotional attachments to the business, to the people who worked in it, and to its customers and suppliers…”

For Zingerman’s this alternative thinking meant eschewing the well-trodden franchising path and imagining a new way to structure their company, all based on the values that inspired them to start Zingerman’s in the first place.

The happy twist is that small giants like Zingerman’s ultimately find financial success beyond their wildest dreams, and they do it by choosing not to focus on money.

Photo: Carl Collins/Flickr

2. Real Company Culture Comes from the Bottom Up, Not from the Top Down

Writing down your values doesn’t create a company culture. It’s when your values are tested and hold true that they gain meaning. And one major test to see if your core values are actually real, as Scott Berkun writes, is to ask whether they are actually being used to make decisions. In other words: “Can an employee say NO to a decision from a superior on the grounds it violates a core value?”

When the junior engineer can veto a hire or a bunch of employees can reject the employment of a co-founder’s family member (like in the story below), values become something more than words on a poster. Upending the power distribution of the traditional pecking order by extending the founder’s veto to your team in a real way is proof of a living, breathing, thriving company culture.

2.1. When CEOS are Proud to be Powerless

At Menlo Innovations, a software company in Ann Arbor, bosses aren’t the major decision-makers — even over how to hire and fire.

When James Goebel and Richard Sheridan founded Menlo, they went all in on their ideas of decentralizing power and rethinking modern management that they’d implemented at a previous workplace. In doing so, they crafted a strong identity and culture at their new company. The “Menlo way” is remarkably open, collective, and democratic.

One of the best tests of those ideas took place when Goebel, who is the COO, had a niece, Erin, who worked as an admin at the company for a few months.

The company’s employees wanted to let her go — having collectively decided that nepotism wasn’t something that fit the Menlo way. Firing someone is always a serious decision, and firing the boss’s family member can be particularly thorny. But the rules applied equally — Goebel wasn’t able to object to the final decision to fire her. “Actually, my niece lives with me,” he told New York Magazine. “And she was really pissed….it was a little frosty for a while.”

For CEOs and bosses reinventing the traditional top-down way of running a company, being a strong leader means less power. Their proudest moment is when they are weakest.

Strong Leaders Grant Veto Power

While research has repeatedly shown that autonomy is crucial for employee happiness and optimal work, the people with the most autonomy tend to be those at the top. They’re usually able to veto any decisions made by anyone lower on the totem pole, no matter how much autonomy is cited as a company value.

For Steve Newcomb, founder of Famo.us and Powerset, granting this power of the “founder’s veto” to all your employees — even over hiring and firing decisions — is crucial. It makes the intention to empower people “with a sense of ownership in the company” and have that be a defining part of your company culture a reality.

When a co-founder at one of his companies brought in a family member to interview for a position, Newcomb let the candidate go through the hiring process because he wanted to see if the veto would take place. It was a real values test, and the company passed with flying colors when someone who would otherwise have the least amount of power said: “No.”

That was the moment Newcomb realized that he’d built an amazing company culture.

“The person that pulled the veto was our most junior engineer at the time,” Newcomb writes. “It was one of the proudest moments I had during the process of building my team. In the face of the power of a founder, I had created a process that made a junior employee not only feel like they had a right to stand up against a founder, but that I actually gave them that power and they used it — ultimately to protect the team.”

The Powerful Stupidity Check

Imagine if Newcomb had sincerely gone along with his co-founder, which could very well have happened for any number of reasons. He could have been busy or uninformed on who exactly the candidate was or felt he was in a position where he didn’t want to hurt his relationship with his co-founder.

When the founder’s veto is exercisable by anyone, it provides an important constraint. As Newcomb points out: “It protects against founders making stupid decisions.”

The very fact that you’re a leader means that you’re at risk of distorted judgment, even as a well-informed, self-aware person. Power not only can change how your brain works, you’re also susceptible to the same irrational cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias, as everyone else. You become convinced that you’re the only one who knows what’s going on — except you’re in the position to make the final decision. Giving others a veto protects against the strong leader’s delusions.

Newcomb points to the healthy consequences of that good decision — that veto “let other junior engineers and even non-technical employees know that when it came to adding a new person to the team, they had the power, the same exact power as a founder, to protect their team.”

2.2. Cells Pods Squads: The Future of Organizations is Small

Think small and you will achieve big things. That’s the Yoda-esque, counterintuitive philosophy that nets Finnish game company Supercell revenues of millions of dollars a day.

So really, how do you build a billion-dollar business by thinking small?

One key is the company’s supercell organizational model. Autonomous small teams, or “cells,” of four to six people position the company to be nimble and innovative. Similar modules — call them squads, pods, cells, startups within startups — are the basic components in many other nimble, growing companies, including Spotify and Automattic. The future, as Dave Gray argues in The Connected Company, is podular.

Still, small groups of people do not necessarily make a thriving business, as the fate of many a fledgling startup warns. What is it about the cells and pods model that presents not just a viable alternative but the future of designing how we work together?

It preserves some of the spark. Let’s go back to Supercell’s terminology. Reflecting both its Latin roots (meaning “small room”) and what we learn about in biology (the smallest structural and functional unit of an organism), cells provide the dynamism and flow of building something together with a few people in the same room. It’s not just that these teams are small, they’re often cross-functional and self-managing, with members totaling in the single digits and probably eating two pizzas.

Achieving big in this podular future requires thinking about what makes that small team magic yield more than a sum of its parts and how to make that synchronize that throughout an entire organization and scalable for sustainable growth.

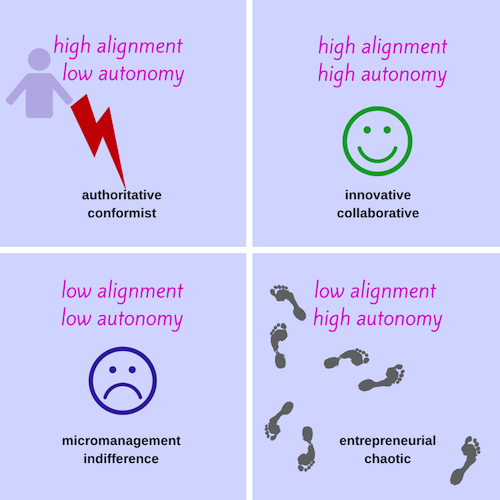

The Autonomy/Alignment Matrix

Autonomy is such a key factor in these small teams that they’re often referred to as startups within a startup. It’s no surprise; autonomy helps you move fast because you don’t get mired in decision-making by committee and inefficient coordination. Autonomy is also incredibly motivating. People crave some degree of control and self-determination to make, build, create awesome things rather than being told what to do.

Yet letting loose a bunch of people and proclaiming “Go forth and be autonomous!” will likely result in chaos, just like mashing a bunch of small startups together to create a larger company wouldn’t work. You have to think about what brings the cells together and how to scale that organizational glue.

The counterpart to autonomy is alignment, as Henrik Kniberg, an agile & lean coach who works very closely with the rapidly growing Spotify, explains.

At Spotify, engineers and product people work within a kind of matrix organization that evolved out of a need to scale agile small teams. Their basic unit or “cell” is called a “squad,” a cross-functional, self-organizing, co-located team of less than eight people that has autonomy on what to build and how. While each squad has a mission to work towards, they still have to harmonize across many levels — on product, company priorities, strategies, and other squads.

The trick, Kniberg explains, is not to frame autonomy and alignment as poles on a spectrum but as dimensions. The goal is high autonomy/high alignment within this framework.

Alignment is what enables autonomy. The stronger the alignment, the more autonomy you can grant because you don’t have to worry that people are going in a million different directions. What does that mean in practice? “The leader’s job is to communicate what problem needs to be solved and why, and the squads collaborate with each other to find the best solution.”

Kniberg sums it up this way: “the key principle is be autonomous but don’t suboptimize.” The company’s overall mission simultaneously takes precedence over individual squad’s and individual’s missions while granting people the ability to direct themselves. It boils down to this: “be a good citizen in the Spotify ecosystem.”

Companies adopt these principles in different ways, according to their needs and cultures. But in studying similarly structured companies, I noticed three ways they create their ecosystem to encourage high alignment/high autonomy and good organizational citizenship.

How to Encourage High Alignment/High Autonomy in Small Teams

1. Don’t Hire Jerks.

If you’re building a high autonomy/high alignment work culture, hiring is a priority concern. You want people in place who will thrive within and contribute to both dimensions. For Supercell CEO Ilkka Paanenen, this is the first and foremost priority: “When you set up a company, the only thing — the only thing — you should care about is getting the best people.”

The “best people” often gets boiled down to what’s the most talented and has the most skill. But that ignores the fact that people must work together. The actual “best people” then have a balance of autonomy and alignment in themselves too. They’re both self-directed and collaborative.

For Spotify, that means filtering out people who don’t really care to align with anything outside of themselves — “the talented jerks,” as Jonas Aman, part of the People Operations team, puts it. “We don’t want to hire people who are very good at what they do but can’t work together with other people.” To do this, they scrutinize how candidates communicate about work they’ve done previously. Do they only talk about themselves? How do they talk about other people? “The best way to predict future behavior is to look at past behavior,” reasons Jonas.

2. Manage Progress and People Rather Than Power

Mini-startups can sound very flat, but alignment, especially as you scale, requires some management, whether they have that title or not.

Take Automattic, which is best known for making WordPress, for example. It currently has over 200 employees, but when it got to about 50 people, the company transitioned from a completely flat structure to the mini-startup collective model. Designated managers, or “team leads” help allocate work and provide direction. As a team lead at Automattic, Beau Lebens describes his job as “keeping the trains running — making sure that as a team we’re focusing, helping schedule priorities, or redirecting things to another team if they don’t make sense for us.”

Beau elaborated further via email — decision-making is:

a mix all the way from ‘the top’ (general strategic direction) down through other team leads (coordination where there’s team cross-over) through me (mainly prioritization and just helping people focus and not get tangled up in other things) to the team, which often decides who will specifically work on what, how to tackle specific projects, how to break it up, etc.

So top-down communication helps provide direction and purpose — the “why” — and small teams decide how to go about finding the best solution — and it’s the team leads who largely make sure everyone’s in alignment.

This more fluid, emergent style of management also applies the progress principle, the fact that making progress is the most powerful motivator. In high autonomy/high alignment company cultures, the job of managers and leaders is to help people make progress and make sure everyone’s on the same page about what progress entails. They do this by providing guidance, support, and making sure people have what they need, rather than a low-autonomy GPS-style management of giving turn-by-turn directions.

3. Enable Self-Service Transparency

Enabling progress on all levels also requires transparency and distributing information. At Supercell, Paananen sends a daily company-wide email with key performance indicators to all employees so that nobody is left in the dark. He explains, “It isn’t restricted to executives, it is the same information released at the same time so we can all figure out on our own what is needed.”

Transparency is one of Automattic’s most prominent values. Beau’s team uses iDoneThis to keep on the same page on what everyone’s working on and to gauge progress all in one place, which helps align his team who’s distributed across multiple time zones. In addition, roughly 80% of all internal communication at Automattic takes place on its P2 blogs, which are organized variously by function, teams, and projects and run on WordPress’s own real-time theme. Rather than information getting hoarded away, decisions and discussions are documented, shared, searchable and viewable to everyone in the company.

When everyone has the knowledge they need at their fingertips, they don’t have to wait around to get to work or make decisions, they can just do it. Distributing information also means distributing power, and sharing knowledge helps align small teams together.

* * * *

People need autonomy, mastery, and purpose to be sustainably motivated and engaged at work, as Dan Pink describes in his book, Drive. Companies like Supercell, Spotify, and Automattic show how Pink’s insights can apply to create not just intrinsic motivation for individuals but people management and collective focus at an organizational level.

People in cellular, agile small teams thrive on autonomy and mastery — which are self-centered elements — but they are also guided, connected, and even elevated through purpose, which Pink describes as “our yearning to be part of something larger than ourselves.” By definition, as organization, there should be a collective purpose, but it’s often unclear or diluted through things like unhealthy politics, mismanagement, or even being at odds with the people you hire.

In building and scaling organizations, communicating, refining, and helping people carry out that purpose is vital to creating good citizens in your work ecosystem. Like pods and squads and cells, it’s about the yin and yang of holding the individual and the collective in your mind at once and thinking about how you can grow together. Supercell’s philosophy is actually a reminder that we’re all made of smaller stuff, that small seeds can grow into giant trees, that small cells and pods can grow, in the right conditions, to achieve greater things.

Credits: Check out Kniberg explaining Spotify’s engineering culture in this video. You can find the alignment/autonomy matrix in his slides here.

2.3. Case Study: How Shopify Crowdsources their Company Bonuses

I’m sure we’ve all worked at companies where the loudest guy gets the biggest bonus. In most companies, compensation is determined by a cabal of execs—guys that you may never have met—evaluating work that happened up to a whole year ago. Bonus compensation ends up being a function of politics, not performance.

51% of employees feel that the performance reviews upon which bonus compensation is based are inaccurate according to a 2011 survey by Globoforce. A 2010 literature survey in Psychology Today concluded that 87% to 90% of employees hate performance reviews because the feedback is not useful, the whole process is stressful, and they’re left demotivated as a result.

Incredibly, despite widespread recognition of its failure, a recent Wall Street Journal article found that 99% of companies still go through the process of ritualized demotivation.

At Shopify, an e-commerce software startup that’s doubled to a 100-employee headcount in a year’s time, they’ve reinvented the process and turned bonus compensation on its head. They distribute bonuses every month — not once a year — and that compensation is determined by peers, not by the management team on high.

Shopify crowdsources their company bonuses.

We spent a week with Shopify at their headquarters in Ottawa, Canada, after the company began using iDoneThis. We learned that their use of iDoneThis was a small part of a bigger philosophy—to put power in the hands of employees, the ones closest to the ground, to make consequential decisions, crowdsource business intelligence, and build their own unique company culture.

To crowdsource company bonuses, the Shopify team built their own internal system called Unicorn. Here’s how it works.

When Serena does something awesome, Daniel gives her thanks by going into Unicorn, logging her accomplishment, and giving her one, two or three unicorns. Everyone in the company sees Serena’s plaudits and can pile on more unicorns if they agree that she did an awesome job.

At the end of month, every employee in Shopify gets allocated a proportion of the company’s profits that are set aside for Unicorn bonuses. Daniel’s allocation goes to Serena and anyone else to whom he’s given unicorns over the course of the month. In other words, Serena’s bonus is determined by the gratitude of her peers for a job well done.

Whereas traditional bonus compensation schemes assume that management knows employee performance better than employees themselves, Shopify’s system seeks the wisdom of the crowd to determine who the top performers are. The upshot is that Unicorn isn’t merely an administrative tool that doles out bonuses, it’s a business intelligence platform for employee performance.

It’s the difference between management hindsight on the one hand and data and genuine insight on the other. CEO Tobi Lutke told me that Unicorn discovered top performers among employees who might otherwise have been overshadowed by more charismatic colleagues.

Perhaps the most amazing fact of Unicorn is that Shopify has transformed the process of workplace feedback, performance evaluation and compensation from a source of fear and dread into a fun way to recognize a colleague’s good work. The power of crowdsourcing is that it can take a back office function like traditional HR and put it into the hands of every person in the company. The result is that Shopify’s company culture of performance, gratitude, and quirkiness is baked into everyday life at the company.

2.4. Case Study: Why Getting Personal Matters for Getting Professional at Karma

Even if transparency is one of your official organizational values, how do you actually make that come true?

Karma has a company culture of openness and sharing, one that reflects its mission to make connecting to the internet easier for everyone. That philosophy of accessibility permeates the company — whether in sharing their journey with their customers, providing weekly — yes, weekly — updates to their investors, or how they get stuff done together.

Company culture isn’t what is written on a poster or slide deck but what happens day-by-day. And what the Karma team has figured out is that transparency doesn’t just happen by itself. The kind of information-sharing it requires depends on people’s willingness to be open with each other, day in and day out — and one of the best ways to do it is tell each other about their day.

The Power of Storytelling At Work

The Karma team seems to intuitively understand how to share with each other, and they do so as a distributed team, with an office in New York and people out in Amsterdam, South Korea, and San Francisco.

What helps them stay connected is by writing asynchronous email updates every day about what they’re up to in iDoneThis. Instead of writing dry, humdrum items that sound like checked-off errands on a to-do list, they approach the updates as an opportunity to share stories of what’s going on and what stood out about the day — including what you got done, funny things that happened, or a customer email that makes or breaks your day.

Paul Miller, a former journalist who recently joined the Karma team, told us how the updates can be like a serialized story. His coworker, Klaas, for example, was trying to get charts to work on Android for the longest time, and every day was a new snippet in the continuing battle. “It was the most entertaining saga,” Paul notes. “The most interesting things are these internal struggles that people have.”

Work Narration Helps People Do Their Job

What the Karma team is doing is narrating their work – describing their experiences and presenting that story to their team. Instead of the painful, artificial process of filling out formal status reports, or having managers monitor their every move, it’s the employees who are the authors, the ones in charge of what they tell and how.

In fact, for Paul, the updates are an opportunity to practice his craft, “As a writer, I’m just always performing when I’m writing. I live for the likes. A like in iDoneThis means more to me than a retweet.”

As Drake Baer writes, narrated work allows people, especially managers, to know what everyone’s up to without spying or nagging them:

Intensely smart management thinker Dion Hinchcliffe calls it narrated work: …[C]reate a palette for people to describe the work they’re doing as they’re doing it, creating a record of all the things that get done, all without eroding the foundation of creativity: autonomy.

And that’s how Karma gets stuff done as a fast-moving, adaptable startup team. CEO Steven van Wel explains, “We give people a lot of freedom to do what they want to do. Everyone has a ton of responsibilities and within Karma, responsibility also means transparency” — including “making sure that everybody else knows what you’re doing.”

The Team that Eats Together

Narrated work allows a glimpse beyond what people are doing into how they’re doing. This transforms what Harvard Business School professor Teresa Amabile calls the “inner work life” (the “constant stream of emotions, perceptions, and motivations as they react to and make sense of the events of the workday”) into common knowledge.

Getting people to share that inner work life and other personal stories doesn’t come naturally. According to Steven, one key to making that possible is their daily family-style team lunches.

In Amsterdam, work lunch is a communal process. People buy groceries, make the food — often sandwiches — set the table, and eat together. When the Karma co-founders first arrived to New York from, they followed what everyone else was doing and ate lunch at their desks. But Steven had to put his foot down at the misery of it all: “No way! I’m behind my desk for eight to ten hours, and I need to get away.”

Now Karma has taken up the Dutch lunch tradition, New-York style. Every day, everyone orders food on Seamless (paid by the company) — and sits down to eat together, family-style. This time isn’t for discussing work at all but everything else, from funny things on the Internet to whatever’s going on people’s lives, like the inevitable Ikea-themed stories that popped up when multiple team-members were moving at the same time.

Getting to know people on a personal level seems like it could be distracting or unprofessional but it actually provides an important foundation of learning how to communicate with each other.

* * * * *

Many co-workers eat lunch together, but for Karma, the ritual is a deliberate part of a larger company culture to build both personal relationships and an open way of working.

Narrating work, telling personal stories, and sharing your inner work life are inherently vulnerable acts that can’t happen without a certain level of trust and comfort. Thanks in large part to daily interaction, work narration, and team lunches, Karma team has developed a foundational camaraderie that makes it possible to support, share, and do great work with one another.

3. Where the Rubber Meets the Road: Living your Values

Company culture means the most when you stand by it in tough times, when making it real costs you something, and when putting it into practice means changing the way you run your business.

The upshot is that by living your values and imbuing them into all aspects of your business, you reinforce them and make them stronger. What results is a transformation of the company that helps it becomes its best, most distinct self.

Here are how some of the strongest brands and cultures in the startup world have done it.

3.1. Case Study: How Buffer Came Out on Top After Getting Hacked

“Aw crap,” I muttered as I looked at my inbox a few weekends ago and saw an email from Buffer CEO Joel Gascoigne with the subject line “Buffer has been hacked — here is what’s going on”.

We rely on Buffer to handle all the iDoneThis social media accounts, so I braced myself for all sorts of toil and trouble as I clicked on the email. It began:

I wanted to get in touch to apologize for the awful experience we’ve caused many of you on your weekend. Buffer was hacked around 1 hour ago, and many of you may have experienced spam posts sent from you via Buffer. I can only understand how angry and disappointed you must be right now….

Fortunately we hadn’t been affected, but I continued to follow updates as they unfolded. Throughout, Buffer was transparent, responsive, and reassuring. They disclosed, accepted responsibility and apologized for the security breach. They communicated not just what they knew but gave us a heads up about their next steps and guidance on what we could do to protect our accounts in the meantime. They also continued posting updates and answering everyone’s questions while resolving the problem.

What happened next is a testament to the strength of Buffer’s response. Joel reports that the pattern of upgrades to paid plans was unaffected and that while there was a spike in downgrades from Buffer’s paid plan, the numbers evened out to normal levels within a few days. Most interestingly, Buffer saw “almost record numbers of signups” during the days of the breach, which Joel surmises was due to the positive press on how they handled the breach.

The supportive response of Buffer customers was amazingly positive and understanding. With every update, people posted encouraging comments, tweets, and messages. As Buffer’s Chief Happiness Officer Carolyn writes in the latest Happiness Report, “I was floored by the patience and extreme kindness of our listeners and followers,” and this goodwill existed largely “due to our dissemination of information as soon as we had it.”

Better Be Human than Have No Comment

It turns out that Buffer’s transparent, prompt, and empathetic response to this hacking incident is the optimal type of reaction for a business responding to a crisis. Research by Adam Galinsky and Daniel Diermeier from Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management shows that the best type of crisis response is one of engagement, meaning that it expresses concern, shares information, and doesn’t close off blame or fault.

One experiment showed the impact of such a response. Study participants read a (made-up) news story about a beverage company alleging a hostile work environment of sexual harassment before they evaluated bottled water from the company in the story. When the company gave an engaged response that such hostile behavior wouldn’t be tolerated and that they were taking the allegations seriously by conducting an investigation — people thought more highly of the company, drank more of its water, and even thought it tasted better.

In contrast, a “no comment” from the company was almost as detrimental as a defensive response denying the allegations and refusing changes to current practices or any investigation. In these two cases, people drank less of the company’s bottled water, said it tasted worse, and were less likely to drink the accused company’s water than an unrelated company’s.

The quality of the company’s crisis response in the eyes of the consumer was powerful enough to affect or “contaminate” what the researchers called “logically unrelated behaviors” such as taste.

In an interesting twist, when researchers presented actual executives with this scenario, they correctly predicted that an engaged response would lead to the most positive reaction but thought that a “no comment” reaction would be better than a defensive response. This “suggest[ed] that executives may be overly optimistic regarding the public’s ability to withhold judgment if they delay providing an official response to the crisis.”

As a customer, it’s delightful to get a response that sounds like it’s from a real human being with real human feelings who will actually do something for you rather than a robot that immediately minimizes the existence of a problem. So Galinsky and Diermeier’s findings that trust requires transparent and caring communication can seem over-obvious. What’s telling is the divide between customers’ experience compared with the point of view of many businesses who still operate as if silence and the appearance of control — even when untrue — is golden. Nobody likes getting left in the dark or getting the run-around.

Creating Transparency Grooves

At the same time, it’s not uncommon for people to operate in “no comment” mode or radio silence themselves — and this may be especially true when their work isn’t going well. It’s uncomfortable and scary to have to admit to having difficulty so people don’t say anything. Yet such times are exactly when others want to know what’s going on so that they can help.

In contrast, Buffer has a company culture of internal engagement, habits of expressing concern and being forthright not only about positives but failures too. Known for its daily practice of extreme transparency, the team regularly shares information including how much salary and equity everyone gets, sleeping stats, specific self-improvement steps, in addition to what everyone is working on. Their default to transparency in how they operate, make decisions, and treat each another provides an integral foundation.

I’ve heard “transparency is easy when things are going well”. This weekend showed me the importance of being transparent when they’re not.

— Joel Gascoigne (@joelgascoigne)

One of the most admirable aspects about the hacking incident is how the entire Buffer team went into all-hands-on-deck mode over a weekend and as a distributed team. They were able to come together and coordinate the technical investigation and customer support — because that’s simply how they operate everyday. Likewise, customer trust on the whole stayed true, not just because of Buffer’s engaged response but because that’s what they’ve been doing all along — being responsive, thoughtful, prompt, and honest through all times, crisis or not.

When the groove of company culture grows deeper with every passing day, such values and practices become second nature and emerge that much more easily when the going gets tough.

3.2. Case Study: This Startup Pays you to Learn How to Code

Learning the new literacy of the 21st century doesn’t come cheap.

Hack Reactor, a code school in San Francisco, costs a breathtaking $17,780 in tuition for 12 weeks of instruction. A semester at Cornell Engineering costs $23,525.

But if you learn to code, the rewards are great. Hack Reactor boasts a 99% graduate hiring rate at an average annual salary of $105,000. A fresh, 22-year-old recent graduate of the computer science from Cornell can expect a salary around $95,670. In short, learning to code is one of the most valuable skills you can develop.

Companies like Wistia are offering a brilliant way around the expensive world of software engineering education. Wistia actively looks to hire non-technical people who want to learn how to code, pays them to work in customer support, and trains them on how to become a software developer. In time, the skills they develop rival what they’d learn in school, the employees are in a position to become professional developers, and they’re well-compensated to learn and grow in a supportive, practical setting.

How Wistia Code School Works

Inside of Wistia, they run what they call Code School. Those who want to learn how to code sign up, and they’re paired with a developer to meet up for weekly one-on-one hour-long lessons over a semester (about 4 to 5 months). Customer champions, for example, might learn Ruby on Rails, the programming language and framework that they use at Wistia, and Javascript.

Instead of culminating in a personal project or a thesis, they work on real-world problems, going straight from learning language theory to fixing actual bugs in the system.

What’s remarkable about the arrangement is that learning to code in a production environment is incredibly motivating to the student and it delivers tremendous value to the company. Before learning to code, the customer champion often isn’t able to solve customer problems. They have to file tickets and ask engineers for help. The best that they can do for customers is say, “I’ve filed a ticket — I’ll let you know when the issue has been resolved.”

It’s naive to think that, while learning to code, a customer champion will be able to fix bugs and solve issues for the customer totally independently. However, learning to code completely transforms the role of support and the internal interaction between support and engineering.

Instead of getting caught up in the process of transactional support — filing issues, closing tickets, and banging out emails — customer champions who learn how to code are empowered to work together with an engineer to find the root cause of problems and solve them. Together, they’re able to make issues go away forever, not just placate a customer until the next one comes along with the same problem. Not only does this process increase transparency and knowledge about the product and how things get done, students gain a gratifying sense of deeper involvement and contribution that spurs them to keep learning.

Starting Your Career as a Software Engineer in Test

It’s not uncommon for a fresh computer science graduate’s first stop out of college to be “a software engineer in test” as it’s called at bigger companies. It’s a great place to learn the basics of testing and producing reliable code, all real-world problems that you don’t often deal with in school.

From there, software engineers in test can get deeper into automation, productivity and testing, or they can move to the application development side as a software engineer.

Unlike hacker school grads who typically build their own small software applications, graduates of Wistia’s Code School cut their teeth on reliability and testing on a large-scale production application. They’ve been so successful that many of them are well-equipped to move on to becoming full-fledged engineers.

* * *

The tech world today isn’t unlike that of finance of the 1950s where opportunities abound for stock room clerks to rise to the top of the organization by picking up the skills they need on the job — where credentials and a past history of success doesn’t matter as much as a hustler’s attitude and a willingness to learn.

For employers, there’s a huge return for those who think long-term and invest in their team. Most startups are software companies, after all, so it’s extremely beneficial to the organization and the customer if everyone in the company can code. With that reality comes the opportunity for those wanting to learn how to code to develop their skills in an environment that’s richer than what school has to offer.

3.3. Case Study: Making Meetings Not Suck

When I first joined iDoneThis, I hated our weekly meetings. They were demoralizing and amorphous. We rambled on, drowning in circuitous discussions about product that led nowhere. The meetings became a chore, making us feel like sulky high school students waiting for the bell to ring.

LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner noticed a similar bad meeting phenomenon of tending to “devolve into a round robin of complaints.” His unconventional solution was to change up the meeting format by promoting something you wouldn’t expect: gratitude.

Gaining Through Gratitude

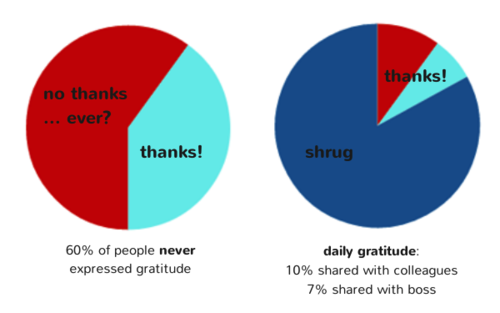

The sad fact is that the workplace is the worst place to find gratitude, according to a 2012 survey by the John Templeton Foundation. 60% of people reported that they never expressed gratitude, or “perhaps once a year.” Only 10% of people share their gratitude every day with their colleagues, a mere 7% with their boss.

The implication is depressing: day by day, people’s effort and hard work get taken for granted. How deflating it feels to toil away, unappreciated. How easy it is, then, to stop toiling.

This swath of the unthanked is missing out on one of the easiest, well-proven ways to make you feel better and less stressed. Psychologist Robert Emmons discovered that when people wrote down five things they were grateful for in a weekly journal for ten weeks, they felt 25% happier. (Amazingly, they even spent more time exercising!)

When people took five to ten minutes at the end of their workday to record three personal or work-related things that went well and why, stress levels and physical health complaints — such as neck and back pain, headaches, fatigue and difficulty focusing — decreased by 15%. Researchers concluded that reflecting on positive events is an overlooked resource, proposing:

“a manager modifying the 3 good things intervention, starting weekly staff meetings by asking employees to share good events from the past week. Focusing on accomplishments, sharing positive experiences, celebrating success, and expressing gratitude would be a change for most organizations and their employees.”

This is exactly the practice Weiner implemented in his weekly executive meetings at LinkedIn. Before getting down to business, everyone goes around and shares one personal and one professional win. Kicking off a meeting through this positive lens of accomplishment, recognition, and gratitude doesn’t just lower stress but also paves the way for a more productive meeting, with higher energy and lower chances of getting bogged down in the negative and irrelevant.

How Gratitude Motivates

According to Weiner, gratitude is the “highest ROI management tool I know … that is available to everyone, costs essentially nothing, and is a proven driver of workplace productivity.” Gratitude doesn’t just make you feel better, it makes you want to contribute more.

Adam Grant and Francesca Gino found that when people received recognition, they helped others for longer, without even being asked to do so. In one of their studies, the director of annual giving visited a group of fundraisers, who had the usually thankless job of asking alumni for donations, and told them, “I am very grateful for your hard work. We sincerely appreciate your contributions to the university.”

That simple expression of thanks resulted in more than a 50% increase in the number of calls in a single week. Gratitude, Grant and Gino explain, increases our feeling of efficacy and self-worth, which sets us up to continue contributing.

Create Channels for Gratitude to Flow

Most of us recognize that we want to feel valued, that it helps us feel engaged and motivated. The Templeton Foundation numbers confirm this, with up to 80% of people reporting that they’d feel better and work harder if they received more gratitude from their boss, and 88% declaring that sharing their appreciation would make them feel happier and more fulfilled.

How come we yearn for the gratitude of others but so rarely share it ourselves — even when we know it’ll feel good? It comes down to expectations and opportunities. When practicing gratitude out loud at work isn’t common, we don’t know if it’s acceptable behavior. This is why leaders can make a real difference by setting examples and providing opportunities for authentic recognition and appreciation to happen.

“Showing gratitude is frequently about catching people doing something right, but it’s critical for leaders to model that behavior so that their teams show each other gratitude,” explains Rich Paret, director of engineering at Twitter. Communicating gratitude cements the team and patterns of great work. “When unexpected challenges arise, my team quickly jumps into action, unconstrained by their traditional ‘roles.’ Through public recognition of this behavior, we see stronger team communication, camaraderie and repeat behaviors.”

“You should always highlight what your coworkers are up to if they’re doing good work,” agrees Melody Kramer, digital strategist at NPR. She created a daily internal newsletter, circulated among 450 people across NPR (and now publicly available), to do just that, strengthening the organization by passing on information about how people were experimenting with social media and digital and what worked.

The new platform also provides a friendly way for people to share and recognize each others’ wins, especially for people who hesitate to show off work they’re proud of. “I can completely understand that it’s very hard,” Melody comments. “You don’t want to be constantly waving around things that you did because that’s not a personality trait that people necessarily like. But there is value in sharing success stories, and if you have a platform for doing that, then people feel much more comfortable.”

Melody sees her job as thinking about how to make the NPR newsroom more productive and make their jobs more enjoyable, even “when they’re being asked to do 8 million things a day.” Being mentioned and sharing, she found, made people happy, which in turn led to more sharing, building up not just appreciation and morale but knowledge. For a large nonprofit with many people but limited resources, that’s powerful.

3 More Ways to Close the Gratitude Gap

The gratitude gap results in less happiness, less wellness, less connection, less knowledge, and yes, most likely less productivity. Gratitude strengthens all around. Every opportunity for gratitude is also a chance to encourage the kind of behavior, attitude, and work you want to see.

Here are three more tips on how to create those opportunities:

Share your wins.

Share your wins by writing them down in a group list, a common space, or out loud at a meeting. Be specific by thinking through the what, why, and who helped to make them happen. This is a practice that’s an utter waste of time if you phone it in, so take authenticity over frequency, quality over quantity.

Make Your Learning Open-Source.

Wins often arise from what we learn. Making what you do and learn more public, as Melody did at NPR, can promote more sharing and involvement. “It’s like open-sourcing your knowledge,” she describes.

Wistia uses a team done list to open-source good things about their work day. Director of Customer Happiness Jeff Vincent explains that this stimulates productive conversation, collaboration, and inspiration that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.

For example, when his coworker Mercer posted, “Did my first real coding in JS”, Dave reached out to give her props and ask about what she did. Mercer ended up sharing her code so that Dave, also new to JavaScript, got to learn. What does Jeff think of this? “An awesome teaching, sharing moment — this is huge!”

Schedule gratitude opportunities.

Here at iDoneThis, we eventually switched over to a new type of weekly meeting, a show-and-tell. Every Friday, we get on videochat and share something we’re proud of that we worked on in the past week or that we learned. As a distributed team, having this deliberate face-time to reflect on wins and talk positively about work helps us learn from each other, feel like we’re building something together, and boosts our morale.

* * * * *

Gratitude has something of a cheesy reputation, invoked on holidays and in sentimental moods, but I’m not talking about grand gestures or greeting cards. I’m talking about the simple act of giving thanks, sharing your appreciation, recognizing others.

Call it what you will, it’s the understanding that you can’t get very far in this world, in work, in life without the help and support of others. It’s a battle cry against the round robin to nowhere as an all-too-common fixture at work — the result of not paying enough attention to people, their dynamics, and not just what they’re doing but how. As Jeff from Wistia says so simply, “Everyone needs support. Everyone needs to know their work matters.”

Image of heart: Judy Merrill-Smith/Flickr

3.4. Case Study: The Extreme Productivity Philosophy that Created Facebook and PayPal

Back in 2005, long before they began approaching $10 billion in annual revenue, everyone thought that Facebook was a cool app, but no one thought that it would ever make any money. Observers laughed at the idea that Facebook could be a real business.

With that backdrop of doubters and detractors, Noah Kagan, employee #30 at Facebook, pitched Mark Zuckerberg with what he thought was a genius idea: prove the Facebook skeptics wrong and show them that the fledgling startup could make real money.

As Kagan recounts the story, Mark listened to the pitch and then wrote out one word on a whiteboard: “GROWTH.” Then he “proclaimed he would not entertain ANY idea unless it helped Facebook grow by total number of ‘users.'”

To Zuckerberg and other Silicon Valley luminaries like PayPal billionaire Peter Thiel, the secret to productivity is this: focus is singular. You don’t get three or four or five. You only get one.

Peter Thiel’s “One Thing” Philosophy of Extreme Focus

Peter Thiel, the first outside investor in Facebook, shares a similar philosophy on productivity and management that he developed while turning PayPal into a billion-dollar company.

In the words of former PayPal executive Keith Rabois, Thiel “would refuse to discuss virtually anything else with you except what was currently assigned as your #1 initiative.” If Kagan had tried to have a meeting with Thiel to pitch a new a new idea, they wouldn’t have even gotten to the whiteboard. Thiel wouldn’t discuss anything but your top initiative.

PayPal’s annual review forms reflected this ruthless focus. You don’t get to brainstorm and make a top 10 list to show off all your accomplishments. All employees got to do was write down their “single most valuable contribution to the company.”

Thiel’s tactics might sound extreme but his insistence on focus as a leader gave the drastic principle real teeth. The counterintuitive thing is that this apparent constraint actually empowered Thiel’s employees. Rabois, one of Thiel’s lieutenants at PayPal, explains:

The most important benefit of this approach is that it impels the organization to solve the challenges with the highest impact. Without this discipline, there is a consistent tendency of employees to address the easier to conquer, albeit less valuable, imperatives. As a specific example, if you have 3 priorities and the most difficult one lacks a clear solution, most people will gravitate towards the 2d order task with a clearer path to an answer.

As a result, the organization collectively performs at a B+ or A- level, but misses many of the opportunities for a step-function in value creation.

(via Is Peter Thiel’s “one thing” management philosophy a good model for startups?)

With distractions cleared away, Thiel allowed every person in the company to seriously pursue their only priority “with extreme dispatch and vigor.” Granting employees a singular focus encourages a clarity of thought and mission that can drive people to perform at A+ levels.

Multitaskers Fail, Those with Focus Succeed

It turns out that for personal productivity, multitasking is one of the worst things that you can do.

Stanford researcher Clifford Nass conducted a study where he gave participants different tasks to do in order to figure out how the brain works — and he was shocked by what he found.

[M]ultitaskers are terrible at every aspect of multitasking. They’re terrible at ignoring irrelevant information; they’re terrible at keeping information in their head nicely and neatly organized; and they’re terrible at switching from one task to another.

On the other hand, researchers have shown having the ability to direct your focus to disregard impulses and distraction — maintaining “cognitive control” in psychological terms — has been shown to be a more powerful long-term predictor of future financial success than IQ and wealth.

In a thirty-year study, psychologists followed the trajectory of over 1,000 New Zealand children to find that those who became the most successful weren’t the smartest or the most well-heeled. They were the children who had shown the greatest self-control. And it’s focus, or control over the mind, that holds the key to self-control.

* * * * *

Focusing on a single, high-impact priority can be the critical advantage for getting things done — whether it’s for yourself or with your team.There are a lot of smart people out there, and a lot of people who have money to spend to make things happen. Your ability to focus and manage yourself amidst the rising tides of tasks, distractions, and ideas is what will set you apart.

To Zuckerberg and Thiel, if you allow yourself to have more than one focus, you’ve already accepted the probability of mediocrity. By its very definition, focus doesn’t function when you’re diffracting your attention.

They considered focus so important that they made it a core part of their company culture, and they lived that core value in their meetings, performance reviews, and decisions on hiring and firing.

Make your focus ruthless. Focus on just one thing, and you’ll put your organization and your own personal productivity on the path to doing your best work and achieving excellence.

4. Build Company Culture through Hiring and Firing

A company is composed of who is hired and who has been fired, which makes it a fundamental part of determining company culture.

It’s painful to not hire someone purely for lack of culture fit when you’re in desperately in need of more hands on deck. It’s just plain tough to fire people who aren’t working out at the company. But these are essential skills you’ll need to build and grow your company culture, because company culture gets built through hiring and firing, whether you like it or not.

4.1. Google’s Most Innovative Employees

Google has long had a reputation for being a place that’s near impossible to get a job if you aren’t a Stanford or MIT grad. They not only asked you for your college GPA, they even asked you what you made on your SAT as a pimple-faced high schooler.

Recently, that’s all changed.

Google’s known for being one of the most data-driven companies in the world and in the area of HR, they’re no different. They even have a department of “people analytics” whose job it is “to apply the same rigor to the people side as to the engineering side.” Google takes this extremely seriously: “All people decisions at Google are based on data and analytics,” according to Kathryn Dekas, a manager in Google’s “people analytics” team.

Their use of data is such a powerful part of company culture that it was able to refute the bias of the company’s founders towards those with an elite educational background that mirrored theirs — that is, top university grads with high GPAs — and it actually resulted in changed organizational behavior.

For years, candidates were screened according to SAT scores and college grade-point averages, metrics favored by its founders. But numbers and grades alone did not prove to spell success at Google and are no longer used as important hiring criteria, says Prasad Setty, vice president for people analytics.

Rather, based on extensive surveys of its work force and performance data, Google discovered that the most innovative Google employees “are those who have a strong sense of mission about their work and who also feel that they have much personal autonomy.”

(Source: https://www.youtube.com/)

Google’s findings have a strong congruence with bestselling author Dan Pink’s work, that the source of human motivation and our best work comes from the drive towards autonomy, mastery and purpose. This can clash with high-prestige and credentialed individuals who are driven by external recognition and rewards, not curiosity and craft.

What you might end up with is people who can follow the rules, but not necessarily those who are after moonshot innovation with extreme dispatch and verve.

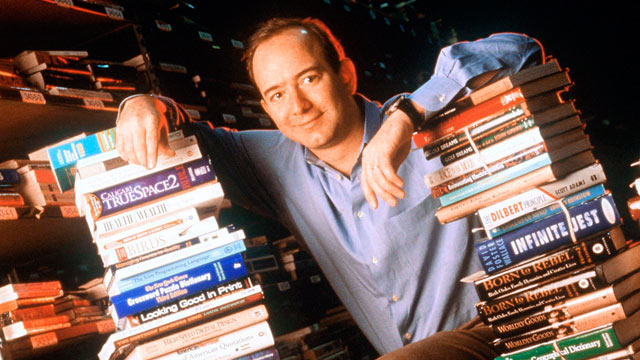

4.2. Case Study: How to Hire Like Jeff Bezos

It’s hard to believe now, but in the early days of Amazon, Jeff Bezos had a tough time hiring.

While he had some extreme methods, he refused to compromise on them even when the company was in desperate need to staff up. Bezos stuck to his guns and turned down candidate after candidate, much to the frustration of his lieutenants.

What must have felt unbearable in the short term turned out to be absolutely critical in the long term, as Amazon built the unique and high-performing company culture that made it the prime tech giant it is today.

1. Tell people that they shouldn’t work at your company

While most managers hire by telling candidates that their company is the happiest and most amazing place on earth, Bezos does the opposite.

Bezos would warn job candidates that “it’s not easy to work here.” Even in 1997, during the dot-com boom, Bezos’s anti-pitch was stark and to the point: “You can work long, hard, or smart, but at Amazon.com you can’t choose two out of three.”

Even though this scared some candidates away, it worked in the long run because those who chose Amazon did so in spite of the anti-pitch. They knew what they were getting into, they had in fact self-selected for the challenge, and so they were exactly the type of people Bezos wanted.

2. Interview 50 people and don’t hire a single one, if that’s what it takes

In the early days of Amazon, Bezos famously said, “I’d rather interview 50 people and not hire anyone than hire the wrong person.”

This takes incredible discipline. It’s very tempting to change your hiring criteria or lower your standards if no one is meeting the bar. Yet standing your ground at this young business stage is particularly critical.

Saying “no” to every potential hire when nobody meets your standards is an extreme act that’s absolutely vital because “cultures aren’t so much planned as they evolve from that early set of people.”

3. Hire failures

When Bezos launched AmazonFresh, its grocery delivery service, he chose a surprising team to lead it. He didn’t choose successful supermarket or delivery executives. He chose failures.

Bezos hired the leaders behind Webvan, a former grocery delivery service that failed spectacularly during the first dot-com era. The thing is, to Bezos, failure isn’t a scarlet letter that you wear around that makes you un-hirable. When you’re innovating, failure isn’t optional. “Failure comes part and parcel with invention,” Bezos emphasized in his 2013 shareholder letter.

Conventionally successful people are often those who’ve played it safe and haven’t tried to innovate. Hire people who’ve failed at doing something bold, because they’re the only ones who’ll succeed at something bold.

4. Ask yourself these three questions:

- Will you admire this person?

- Will this person raise the level of effectiveness?

- Along what dimension might this person be a superstar?

Back in his 1998 letter to shareholders, Bezos talked about how he started Amazon to change the world. If your mission is to build an app, you need to bring on people who can build apps. If your mission is to change the world, you need to think long term and hire extraordinary people.

By asking hiring managers to consider these three questions, Bezos ensured that new employees would not only meet an incredibly demanding standard but add value to and enrich the growing team in the long term.

In order to do great things and make history, you have to keep building up.

5. Set the Bar High

In Bezos’s own words, “Setting the bar high in our approach to hiring has been, and will continue to be, the single most important element of Amazon.com’s success.”

From the very beginning, “Jeff was very, very picky,” says Nicholas Lovejoy, Amazon’s fifth employee. From five employees to now over 100,000, that pickiness has persisted, which has allowed Amazon to build a company culture that lasts and improve the quality of the company with each hire.

In all hiring criteria, Bezos held candidates to the highest standards and it proved to be the basis of the company’s success. Bezos’s motto is this: “every time we hire someone, he or she should raise the bar for the next hire, so that the overall talent pool is always improving.”

When employees visualize the company in five years, according to Bezos, they should be able to look around and say, “The standards are so high now — boy, I’m glad I got in when I did!” The result is a company that evolves to become better and stronger.

5. Find Your Company’s Voice for Internal and External Communication

There’s no single best way to communicate internally with your team or externally with customers and stakeholders.

How you and your colleagues communicate is a product of your company culture, which means that the best way to do it is the way that’s true to who you are as a company. That’s how you’ll develop your individual voice and innovate where others just try to copy the leaders.

Here are how some of the best companies developed unique ways to communicate, in line with their company cultures, that resulted in significant innovations in how companies are designed and built today.

5.1. Case Study: How Amazon Makes Small Teams Work with Terrible Communication

Amazon is a mess. In the words of one former Amazon.com engineer: “their hiring bar is incredibly inconsistent across teams,” “their operations are a mess,” “their facilities are dirt-smeared cube farms without a dime spent on decor or common meeting areas,” “their pay and benefits suck,” and “their code base is a disaster, with no engineering standards whatsoever except what individual teams choose to put in place.”