A Practical Guide to Transparency for Startups

Join the movement that’s changing how companies are grown and run

By law, a public company can’t be transparent about how it operates, but a startup can. The ability to be transparent is an advantage unique to startups and, done right, it can drive company culture, employee happiness & retention, marketing, community building, and all other aspects of your business.

Moreover, transparency is an essential movement that’s changing the way that companies are built because it has the potential to make work more human and fulfilling.

In this guide, we cover why transparency is so valuable and important, and we give you concrete advice on how to make transparency real in your company using examples from how the best startups are doing it today. After you get a chance to read our guide, we’d love to hear what you think on Twitter at @idonethis.

Table of Contents

- Nowadays, You’re Hiring People to Think

- The Transparency Paradox

- The Backbone for Effective Transparency: Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose

- The Inherent Fairness of Salary and Performance Transparency

- Work In Public

1. Nowadays, You’re Hiring People to Think

In many companies, your manager will know the team’s and company’s objectives, but you won’t. He may keep crucial information from you so that he can consolidate decision-making power.

Not so at Qualtrics, the extraordinary Provo, Utah-based company that did $50M in revenue, raised $70M from elite venture capital firms Sequoia and Accel, turned down a $500M acquisition offer, and grew its headcount to nearly 300 employees in 2012.

At Qualtrics, transparency is perhaps the company’s most important value for one simple and obvious reason—”Nowadays, you’re hiring individuals to think.”

For employees to think for themselves, they need information—and that comes from transparency. At Qualtrics, not only can every employee see the company’s objectives and every employee’s objectives, every employee can also see what every employee has gotten done recently, performance reviews and ratings for all employees, meeting notes from all meetings that have taken place, and even the office’s security camera footage.

We took our best product guy and some of our best engineers and built a system internally to help scale our organization by knowing everyone’s objectives in the company. We have five objectives annually for our company, and everyone goes into the system each quarter to put in their objectives that play into those broader goals.

…

We have another system that sends everyone an e-mail on Monday that says: “What are you going to get done this week? And what did you get done last week that you said you were going to do?” Then that rolls up into one e-mail that the entire organization gets. So if someone’s got a question, they can look at that for an explanation. We share other information, too — every time we have a meeting, we release meeting notes to the organization. When we have a board meeting, we write a letter about it afterward and send it to the organization.

When everyone’s rowing together toward the same objective, it’s extremely powerful. We’re trying to execute at a very high level, and we need to make sure everyone knows where we’re going.

Qualtrics is taking to an extreme what many tech companies have done to eliminate the manager-as-a-single-point-of-failure antipattern of corporate organization. Transparency gives the power of self-determination to every employee in the organization.

1.1. Case Study: How Silicon Valley Companies Scale their Teams with Transparency

The wonder of Silicon Valley has been its rich history of producing incredibly capital efficient companies operating at massive scale. No doubt part of that achievement lies in the capital efficiency of software engineering itself where technology gives incredible leverage to create and disrupt established industries. Nevertheless, as a company scales, individual engineers need to work together in concert which results in the industry-agnostic problem of people management.

Unique from other industries, Silicon Valley’s natural inclination is not simply to find a solution to people management, it’s to create a scalable management model. Of course, technology is the natural place to turn.

During Google’s growth stage, Larry Schwimmer, an early software engineer, stumbled upon a solution deceptively simple, but one that persists to this day at Google and has spread throughout the Valley. In his system called Snippets, employees receive a weekly email asking them to write down what they did last week and what they plan to do in the upcoming week. Replies get compiled in a public space and distributed automatically the following day by email.

A number of the top Silicon Valley startups have similar processes. At Facebook, they have a system called Colbert where weekly check-ins are logged. Square employees, for example, send weekly reports directly to the COO Keith Rabois. The elite engineering shop Palantir requires a weekly email to managers detailing what got done last week and what’s planned for the upcoming week.

The Snippets process at any scale is a compelling productivity solution, and companies of all sizes have adopted it — some, like SV Angel, rich in Google DNA, do daily snippets. The process forces employees to reflect and to jot out a forward-looking plan for getting stuff done, all while requiring a minimal disruption in the employee’s actual work.

Setting aside time on a daily or weekly basis to reflect on the day is a powerful productivity hack. In The Progress Principle, Harvard Business School professor Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer showed the counterintuitive conclusion that progress toward a meaningful goal is the #1 motivator for employees at work, not financial motivation or downward pressure. Professor Amabile prescribes 5 minutes per day of reflection, religiously protected by bosses, centered around the progress and the setbacks of the day. Simply put, employees connected to their work and its progress are happier and more productive.

On the flip side, Snippets works because it has a minimal disruption in employee flow because it works asynchronously and without facetime. It allows for a maker schedule — large blocks of time dedicated to concentrated progress on work — rather than breaking up an engineer’s day into a manager’s schedule to suit a manager’s need to manage. At Palantir, they do email snippets because they have a very strong culture against meetings. In addition, email as an interface avoids the issues with, for instance, CRMs, where employees spend valuable time logging into a system and entering highly structured information or they don’t use it at all.

Google turned periodic email updates as a process into a scalable management solution, leveraging technology, through automation, data storage and data retrieval. An individual’s Snippets are transparent across the organization and are linked to an individual’s internal resume in its MOMA system which connects individual employees to the work of team members and others within the company. It can kill political squabbles, the core problem of people management, by providing a record of what’s been done.

Put differently, Snippets is a management process that scales because transparency means that individual engineers can manage themselves and individual engineers can manage each other without having to go through a middleman. It’s the disruptive power of peer-to-peer for management centered around atomic units of work.

Silicon Valley’s focus of work around the work itself is still an ongoing competitive advantage. Compare it to the East Coast and you’ll see a stark contrast in the importance of dress and facetime at the office. Being work-centric means focusing manically on how to formulate process to eliminate all the cruft. Most engineers at Google, Zynga, Palantir, Square, etc. do often end up finding the process of Snippets and OKRs to be annoying and unnecessary — at the same time, many of them admit that they were their most productive when they closely tracked their Snippets and OKRs (objectives and key results) and that much of the autonomy and freedom that’s characteristic of top software engineering shops in the Valley could be attributed to Snippets doing its work of people management secretly, in silence.

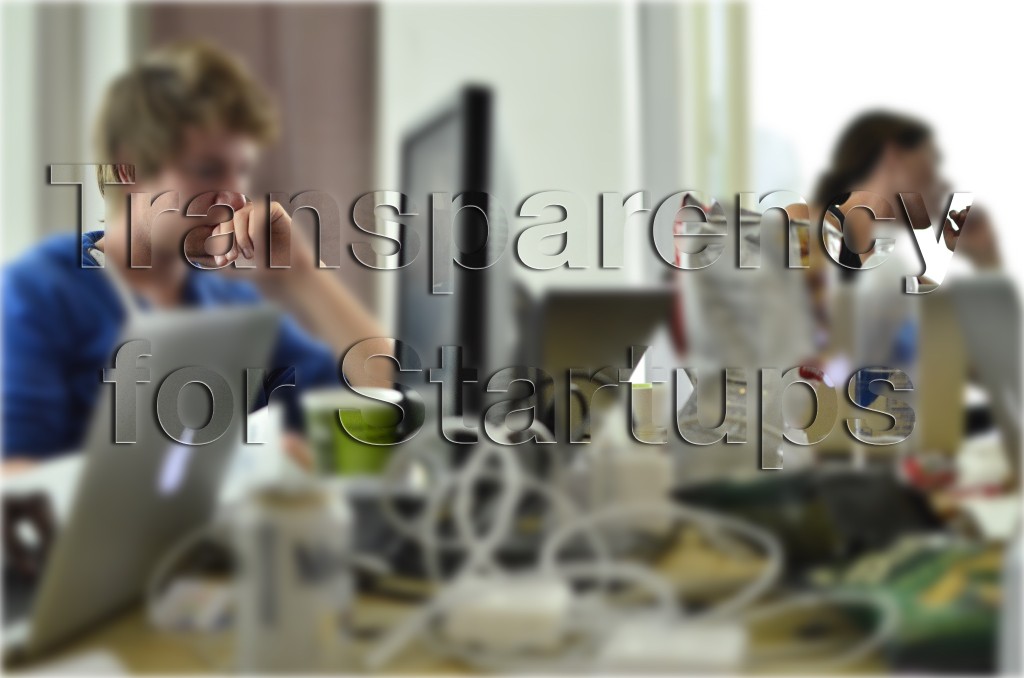

1.2. Case Study: How Transparency Helps Buffer Works Smarter, Not Harder

Buffer stands out among startups not just for its success in building a great social media sharing tool but in fashioning a company culture focused on making work fulfilling, impactful, and enjoyable. What’s fascinating is that they do this as a completely distributed team, spread across multiple countries and time-zones.

![]()

Treat People in the Best Way

Co-founders Joel Gasciogne and Leo Widrich set the foundation for Buffer’s culture according to the tenets of Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. Carolyn Kopprasch, Buffer’s Chief Happiness Officer translates what that means for Buffer’s modus operandi: “We want to treat people in the absolute best way we can, and that includes co-workers, vendors, and customers.”

It also includes how the Buffer employees treat themselves. With a unique self-improvement program, they share their progress on anything from time management to healthy eating with their teammates, spurring conversations about different lifehacks and routines. Michelle Sun, Buffer’s growth and analytics expert, tracks fitness routines and getting up early while Leo has been making strides with learning how to code.

Co-workers become a collective accountability partner for future plans like blogging or exercising, and more importantly, they become an incredible support system. Instead of looking askance when you’re doing work to do something to take care of yourself, you receive encouragement. “If you’re trying to work on your health or your fitness or your happiness level, that affects work a lot too,” Carolyn explains.

Work Smarter, Not Harder at Buffer

It’s not surprising then, that one of the company’s mantras is to work smarter, not harder — taking time to review what’s working and how to improve operations. As a remote team, Buffer needed a better way to stay on the same page. Previously, everyone would get on a daily group Skype call in which each person would take three minutes to talk about what they did, how their co-workers could help, and their improvements. With the team growing larger and the standup process proving unwieldy over email, Buffer turned to iDoneThis.

Leo remarks, “It allows us to track performance, which easily gets lost in a chat room or an in-person standup. If new people come on board, they can look through and see what has been worked on. And of course, it’s amazing to keep in sync with everyone, working as a remote team. iDoneThis is invaluable to us and has changed our productivity for the better.”

Michelle agrees, “It’s a way to understand what teammates are working on, and every time I read people’s iDoneThis, I feel connected with the team.” Where iDoneThis shines, for Carolyn, is the ability to comment and have chronicled conversations about her teammates’ work and improvement practices. “I think that’s one of the biggest things. It’s not just reporting what we’ve done. It’s asking, ‘oh tell me more about that.’”

iDoneThis is a natural fit for Buffer’s culture, but Carolyn points out that iDoneThis has helped them to work even smarter. Holding more traditional standups over video chat meant that “if you jump in and talk about something that somebody just said, you’re basically interrupting their three minutes. So what we would actually do is not ask that many questions.” Now the team can communicate asynchronously — asking, commenting, interacting — without feeling like they’re butting in.

Transparency Fosters Tight-Knit Teams

The extreme transparency that Buffer practices in terms of sharing information from sleep habits to how much salary and equity everyone gets is not without feelings of vulnerability. But what they gain is an incredible feeling of connection. In the Buffer universe, where the personal flows right into work and vice versa, it’s their collective care, attention, and support that binds and strengthens the company.

“When somebody will say to me, ‘you didn’t really get very much deep sleep yesterday. Maybe you can try taking a bath before dinner,’ and you’re like, ‘where am I? Am I at work?’” Carolyn laughs. “It’s unique. It takes a certain type of person to really like that, but having a team that’s really interested in keeping you accountable to your own self-improvement is kind of a wild thing. It’s awesome and a little bit crazy sometimes.”

2. The Transparency Paradox

The rule is one operator per station. But when nobody’s watching, there might 17 people for 13 stations on the assembly line at one mobile phone manufacturing plant in Southern China.

When managers comes around, though, they’ll see 13 operators, one for each station, exactly as prescribed by the leaders. Even with company values like learning and continuous improvement, this plant’s employees scrambles to hide exactly the kinds of refinements and creativity that management seeks.

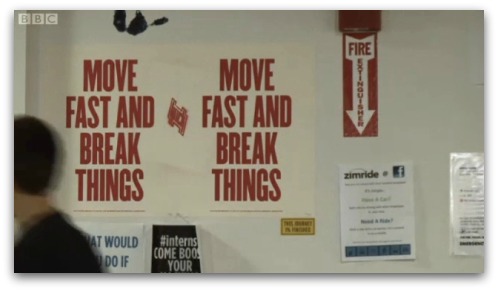

Transparency is often touted as a vital ingredient for the best teams. And it’s true. For people to move fast and think for themselves, they need ready access to the information they need to do their job. Failing to provide a foundation of common knowledge and creating an uneven distribution of information opens the door for inefficiency and unhealthy power imbalances.

But the transparency paradox arises when there’s no trust and autonomy. Actually, it’s more like counterproductive monitoring — one-sided visibility to benefit the manager’s curiosity rather than equip the employees to do their best work.

2.1. When Transparency Makes People Hide

As Ethan S. Bernstein, Harvard Business School professor, discovered in his study of that Southern Chinese plant, organizational transparency may be counterproductive, incentivizing people to hide. When you’re watching your employees like a fox, you can drive them underground.

For his study, Bernstein embedded Chinese-born Harvard undergraduates at the manufacturing plant. Their new peers took them aside and discreetly showed them methods and tricks that improved on the by-the-book training to accomplish tasks, keep production going, and make the work faster, easier, and safer.

Meanwhile, the whole reason managers at this plant supposedly cultivated workplace transparency was to foster learning and continuous improvement. Everything about the set-up and environment — from the display of output and quality numbers to different-colored caps and clothes indicating roles — were carefully designed to, first, help figure out the best way to do something, and second, be able to spread that information quickly to other lines.

Yet what happened was that the employees hid their best, most innovative ways of doing things. They also instructed the embedded Harvard newbies to alter their methods when observed or when things weren’t too busy.

Otherwise, they explained, the managers will “get mad” and yell at them. So when employees saw supervisors hovering — they resorted back to doing things according to code, and predictably slowed down. This combination of top-down observation and transparency then caused productivity to fall, and the “suggestion boxes on every line remained empty.”

2.2. How to Use Trust and Autonomy to Channel Change

Employees hid even though they knew the best way of doing things and productivity would decrease, because experience had taught them the cost of deviating from managements’ expectations.

The plant employees explained, either they would have to stop to justify why the new methods were better in ways that the managers understood, or get in trouble from diverging from the standard — both of which stood in the way of actually getting stuff done on busy, demanding assembly lines.

How employees perceive their autonomy is crucial to eliminating the transparency paradox. It’s pretty clear that autonomy doesn’t mean anything if you get penalized for trying new things. As additional research from the University of Illinois’s Gopesh Anand and Dilip Chhajed corroborates, trust has to flow in both directions. Otherwise, as they write:

any latitude that employees have as a result of autonomous job design will be used to make ad hoc changes to work processes rather than to channel such changes through systematic continuous improvement.

Basically you have to create a safe environment for experimentation and failure. As an operator who’d contributed many of the new improvements on the line explained to Bernstein: ‘We have all of these ideas . . . but how do we feel safe to try them? We’ll experiment as long as the consequences aren’t so great. As long as the price we pay isn’t so great.’’

Employees can recognize in a second when higher-ups don’t have the same depth of knowledge of the work on the ground. That means managers have to be careful of becoming their own obstacle — setting rules and requirements because they think they’re the smartest person in the room — without completely understanding what’s going on.

Those extra operators on the line? They provided much-needed help whenever the line fell behind and enabled employees to meet increased targets that were determined by managers and kaizen engineers who’d pitched in with production to come up with the new numbers.

If you want transparency to be a truly beneficial practice, back it up by supporting your employees’ progress rather than delivering edicts and only watching for mistakes. When you impose the transparency paradox’s costs on experimentation, innovation, and even making mere suggestions, everyone loses out on crucial information and better ways to work.

2.3. Are You an Unwitting Audience to Productivity Theater?

A productive office is supposed to be a buzzing hive of activity, right?

But as a manager, a workplace that’s always humming with constant activity is not what you want to see — because it’s a sign that something has gone awry. It means that people are putting on a show to look busy all the time.

You know the trick: when someone walks by, you quickly switch tabs to bring up the spreadsheet or report you’re supposed to be working on, or engage in theatrics like looking very annoyed or walking briskly like you’re a very important person who can’t be bothered.

Welcome to Productivity Theater. It’s what you see when there’s transparency but no trust and autonomy.

Even though it’s impossible for human beings to be working nonstop, that’s what’s expected at the workplace. Looking busy becomes how you get recognized for doing a good job. The result is a show put on for the managers — and proceeds largely according to their expectations, scripts, and direction.

The Fruitless Posing of Productivity Theater

One of the biggest challenges of being the boss is that you always want to know what’s going on. Your job relies on information in order to be able to deal with problems, strategize, and make decisions, and it’s why leaders like Andy Grove spent the larger part of his day information-gathering.

Yet, as Harvard Business School professor Ethan Bernstein discovered, this information-gathering quest can be exactly what drives people to put on a productivity theater show.

When Bernstein studied a Chinese mobile phone factory, he was surprised to find that employees devised better, easier, safer ways to perform tasks, but when managers came around, they returned to doing things by the book. Even though the company was trying to build an open culture of learning and continuous improvement, it left out the crucial factors of trust and autonomy. Employees ran into obstacles and discouragement when bringing things up, since the only “acceptable” changes came from the top.

The intended openness turned into an obstacle because it didn’t serve employees and slowed them down. “We assume that when we can see something, we understand it better,” Bernstein explained to the Harvard Business Review. “In this particular environment, and perhaps many others, what managers were seeing wasn’t real. It was a show being put on for an audience. When the audience was gone, the real show went on, and that show was more productive.”

Overcome Managerial Confirmation Bias

The problem is that people already see what they want to see. If everyone seems busy all the time, it tends to reflect well on you as a manager for running a tight ship.

But as one of the plant operators in Bernstein’s study explains, this is just a coping mechanism to keep things running smoothly — rather than make improvements, innovating, and trying new things. “Everyone is happy: Management sees what they want to see, and we meet our production quantity and quality targets.”

When asked about what motivated them to hide their improved techniques and experiments, the plant workers pointed to the lack of knowledge that many middle managers have of what jobs actually entail:

People from above don’t really know what they are doing. They set all these rules, but they have no idea how it actually operates down here. Sure, process engineers time these things and set all of these requirements, but they have no idea how people operate.

Catering to the confirmation bias of managers is counterproductive. Inherent to the job of managing others is that you’re going to be somewhat removed from the work being done. Your productivity relies on helping your team make progress, not driving that knowledge further underground.

The appearance of continuous activity means that there’s either a show going on due to a lack of support and trust or people are struggling to manage their time effectively — both exactly the kind of issues that make up a manager’s job.

Don’t Short-Circuit Transparency

The point of transparency isn’t one-way observation but openness, increasing ownership and empowering the very people doing the work. Here’s three things to consider to protect against productivity theater:

- Define productivity in terms of results rather than facetime. Stop measuring things in terms of hours and mere presence, and look instead at results. Relying on face time as a way to measure performance incentivizes presenteeism over efficient, effective work.

- Create zones of privacy. In his study, Bernstein found that creating smaller zones of privacy — blocking off certain assembly lines with curtains, for example — actually allowed transparency to do it work. Since the workers felt safe to experiment and not put on a show, they became more productive and were more comfortable sharing their improvements. In open offices and transparent work cultures, make sure there are physical and mental spaces where managers aren’t hovering.

- Find out what people need to manage their energy. Willpower, productivity, and motivation wax and wane during the day, so doing your best work means having the autonomy to recharge when you need to, without having to put on a show of looking busy.Incentivize people to take breaks, get away from the desk, and exercise.

That could mean furnishing coffee and healthy snacks, having team lunches away from people’s desks, or offering a stipend for a gym membership. You could even provide dedicated napping spaces like Hubspot, which has an entire nap room that can be booked like a conference room, or Buffer, which has bunk-beds in their SF headquarters.

* * * * *

If you don’t trust your employees, then you can’t trust what you see.

And the more you try to gain visibility in a trust-less environment, the more your employees will resent efforts to monitor and observe, especially when cloaked in the friendly language of openness and transparency. They’ll hold themselves back and end up distrusting you in return.

Photo: Jason Brush

3. The Backbone for Effective Transparency: Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose

Given a choice between solving puzzles for free or for pay — which would you pick?

If you want to stay motivated and solve more puzzles, the surprising thing is that you should do them for free.

In the early 1970s, psychologist Edward Deci wanted to study how money affects motivation. In one experiment, he paid one group $1 (that’s about $6 today) for each puzzle solved within three sessions, while the control group received no payment. In the middle of each session was an eight-minute free period in which people could continue puzzling, read magazines, or otherwise spend the time how they wished.

It was the paid group who chose to spend less time working on puzzles in the free periods. The extrinsic monetary reward made them lose intrinsic motivation, where the reward is the activity itself.

Over forty years later, managers still rely on the old model of dangling external rewards like money and prestige to motivate their people — but in today’s era of knowledge work, this model is increasingly misguided. If you think your people are going to continue to put in their best efforts with monetary rewards, you’re sabotaging the most powerful sources of motivation.

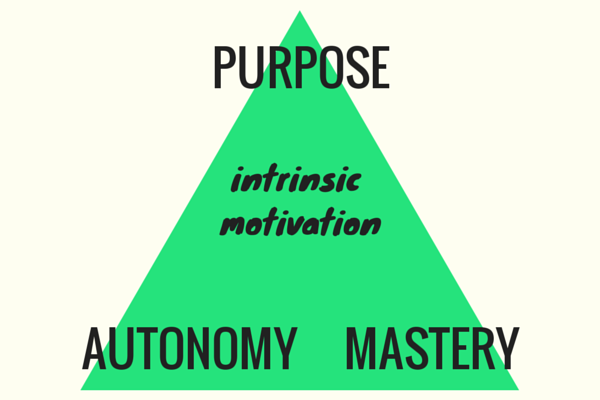

Instead, as Daniel Pink explains in his book, Drive, the three basic sources of motivation — autonomy, mastery, and purpose — come from within.

While this assumes fair compensation as a baseline — the fact is that in harnessing intrinsic motivation, you feed deep-seated human psychological needs. That’s incredibly compelling and it’s an essential backdrop to having a transparent organization. Here’s a basic refresher on these three limbs of intrinsic motivation and what managers can do to drive transparency and help people become more motivated, productive, and happy.

3.1. Autonomy: Help people direct themselves

People want to feel like they have a choice in what they’re doing, that they’re in some way determining their own fate rather than having to follow scripts set out by others.

As a manager, you hold the keys to increase this sense of choice by providing what Deci and psychologist Richard Ryan call “autonomy support.” A major departure of the command-and-control style of management, this involves acknowledging people’s perspectives, encouraging choice and self-initiation, providing relevant information, and being responsive rather than dictatorial.

The effects are great. In a 2004 study, Deci and Ryan discovered that employees that receive autonomy support are better performers, and happier to boot. Provide some choice over how to do work and support people with the frequent feedback and resources they need to get the job done. At companies like Reddit, Buzzfeed, and Foursquare, they use a system that originated at Google called Google Snippets to distribute information across the whole company on what people are working on — helping people stay on the same page. This kind of transparency gives autonomy to people to do their best work instead of having to stop and hunt down the information they need or wait to receive it from gatekeepers.

3.2. Mastery: Invest in your people

Getting better at something is inherently satisfying and motivating. Making progress at learning a language or an instrument, for example, fuels the fire to keep getting better. If you feel like you’re getting stuck and running in place, failing to grow in some meaningful way, it’s natural for interest to fade and effort to flag.

Failing to capitalize on the motivational benefits of improvement and mastery is a major mistake. More and more, however, employers aren’t making the effort to train, grow, and broaden their employees’ skills. Such investment has a mutual benefit: investing in your people is a way to build for an organization’s long-term future.

Companies like Spotify and Wistia invest in their people with deliberate programs to teach new skills and build on existing ones. Wistia runs a code school to teach employees how to code using real-world problems. At Spotify, they believe in three-dimensional development, that you can develop in more ways than moving up the corporate ladder. They provide structured opportunities to learn at trainings, workshops, and teach their co-workers. You don’t have to start a whole new training scheme to help people gain mastery at work. Provide coaching and frequent feedback to encourage learning and continuous improvement.

3.3. Purpose: Connect work to a greater cause

Having a larger purpose to work towards sounds almost like a luxury in the world of work — but it’s the deepest well of motivation. Purpose gives you a reason to stretch, explore, and keep at it. Contrast that with the disconnection many people feel about their job — at best, you’re in it for the paycheck — but if you don’t know why you’re doing something, what will drive you onwards and upwards?

As a manager, you want to help your team get up in the morning and feel like going to work because they have a purpose to work towards. It can be easy to forget about purpose as you get stuck in project details and analyzing metrics. Consider how often you communicate and connect work to purpose, values, and people. Help employees figure out the high-level “why” question. What’s the point of doing this task? Who does it affect? Why does it matter?

Nearly ten years ago, Tony Hsieh, CEO of Zappos sent out an email to employees, investors, and partners in which he explained that the purpose of a company like Zappos wasn’t to maximize short-term profits. It’s to “build a company culture and consumer brand that is centered around service, not the shoes or the handbags.” In continuing to reinforce and develop its inspiring purpose, Zappos motivates its people not just to get up in the morning and come to work with fewer grumbles — but to build something great.

* * * * *

What drives our best work is intrinsic motivation, which sustains more deeply than any external reward can. As Pink writes:

Human beings have an innate inner drive to be autonomous, self-determined, and connected to one another. And when that drive is liberated, people achieve more and live richer lives.

People often fantasize about dream jobs, but often there are intrinsically motivating things we can do as individuals and managers to bring out and nourish autonomy, mastery, and purpose to turn a bunch of tasks and to-do lists into something more meaningful.

3.4. Case Study: Cells, Pods, and Squads—The Future of Organizations is Small

Think small and you will achieve big things. That’s the Yoda-esque, counterintuitive philosophy that nets Finnish game company Supercell revenues of millions of dollars a day.

So really, how do you build a billion-dollar business by thinking small?

One key is the company’s supercell organizational model. Autonomous small teams, or “cells,” of four to six people position the company to be nimble and innovative. Similar modules — call them squads, pods, cells, startups within startups — are the basic components in many other nimble, growing companies, including Spotify and Automattic. The future, as Dave Gray argues in The Connected Company, is podular.

Still, small groups of people do not necessarily make a thriving business, as the fate of many a fledgling startup warns. What is it about the cells and pods model that presents not just a viable alternative but the future of designing how we work together?

It preserves some of the spark. Let’s go back to Supercell’s terminology. Reflecting both its Latin roots (meaning “small room”) and what we learn about in biology (the smallest structural and functional unit of an organism), cells provide the dynamism and flow of building something together with a few people in the same room. It’s not just that these teams are small, they’re often cross-functional and self-managing, with members totaling in the single digits and probably eating two pizzas.

Achieving big in this podular future requires thinking about what makes that small team magic yield more than a sum of its parts and how to make that synchronize that throughout an entire organization and scalable for sustainable growth.

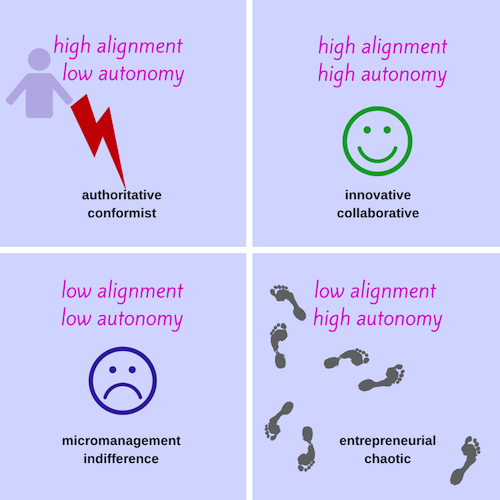

The Autonomy/Alignment Matrix

Autonomy is such a key factor in these small teams that they’re often referred to as startups within a startup. It’s no surprise; autonomy helps you move fast because you don’t get mired in decision-making by committee and inefficient coordination. Autonomy is also incredibly motivating. People crave some degree of control and self-determination to make, build, create awesome things rather than being told what to do.

Yet letting loose a bunch of people and proclaiming “Go forth and be autonomous!” will likely result in chaos, just like mashing a bunch of small startups together to create a larger company wouldn’t work. You have to think about what brings the cells together and how to scale that organizational glue.

The counterpart to autonomy is alignment, as Henrik Kniberg, an agile & lean coach who works very closely with the rapidly growing Spotify, explains.

At Spotify, engineers and product people work within a kind of matrix organization that evolved out of a need to scale agile small teams. Their basic unit or “cell” is called a “squad,” a cross-functional, self-organizing, co-located team of less than eight people that has autonomy on what to build and how. While each squad has a mission to work towards, they still have to harmonize across many levels — on product, company priorities, strategies, and other squads.

The trick, Kniberg explains, is not to frame autonomy and alignment as poles on a spectrum but as dimensions. The goal is high autonomy/high alignment within this framework.

Alignment is what enables autonomy. The stronger the alignment, the more autonomy you can grant because you don’t have to worry that people are going in a million different directions. What does that mean in practice? “The leader’s job is to communicate what problem needs to be solved and why, and the squads collaborate with each other to find the best solution.”

Kniberg sums it up this way: “the key principle is be autonomous but don’t suboptimize.” The company’s overall mission simultaneously takes precedence over individual squad’s and individual’s missions while granting people the ability to direct themselves. It boils down to this: “be a good citizen in the Spotify ecosystem.”

Companies adopt these principles in different ways, according to their needs and cultures. But in studying similarly structured companies, I noticed three ways they create their ecosystem to encourage high alignment/high autonomy and good organizational citizenship.

How to Encourage High Alignment/High Autonomy in Small Teams

1. Don’t Hire Jerks.

If you’re building a high autonomy/high alignment work culture, hiring is a priority concern. You want people in place who will thrive within and contribute to both dimensions. For Supercell CEO Ilkka Paanenen, this is the first and foremost priority: “When you set up a company, the only thing — the only thing — you should care about is getting the best people.”

The “best people” often gets boiled down to what’s the most talented and has the most skill. But that ignores the fact that people must work together. The actual “best people” then have a balance of autonomy and alignment in themselves too. They’re both self-directed and collaborative.

For Spotify, that means filtering out people who don’t really care to align with anything outside of themselves — “the talented jerks,” as Jonas Aman, part of the People Operations team, puts it. “We don’t want to hire people who are very good at what they do but can’t work together with other people.” To do this, they scrutinize how candidates communicate about work they’ve done previously. Do they only talk about themselves? How do they talk about other people? “The best way to predict future behavior is to look at past behavior,” reasons Jonas.

2. Manage Progress and People Rather Than Power

Mini-startups can sound very flat, but alignment, especially as you scale, requires some management, whether they have that title or not.

Take Automattic, which is best known for making WordPress, for example. It currently has over 200 employees, but when it got to about 50 people, the company transitioned from a completely flat structure to the mini-startup collective model. Designated managers, or “team leads” help allocate work and provide direction. As a team lead at Automattic, Beau Lebens describes his job as “keeping the trains running — making sure that as a team we’re focusing, helping schedule priorities, or redirecting things to another team if they don’t make sense for us.”

Beau elaborated further via email — decision-making is:

a mix all the way from ‘the top’ (general strategic direction) down through other team leads (coordination where there’s team cross-over) through me (mainly prioritization and just helping people focus and not get tangled up in other things) to the team, which often decides who will specifically work on what, how to tackle specific projects, how to break it up, etc.

So top-down communication helps provide direction and purpose — the “why” — and small teams decide how to go about finding the best solution — and it’s the team leads who largely make sure everyone’s in alignment.

This more fluid, emergent style of management also applies the progress principle, the fact that making progress is the most powerful motivator. In high autonomy/high alignment cultures, the job of managers and leaders is to help people make progress and make sure everyone’s on the same page about what progress entails. They do this by providing guidance, support, and making sure people have what they need, rather than a low-autonomy GPS-style management of giving turn-by-turn directions.

3. Enable Self-Service Transparency

Enabling progress on all levels also requires transparency and distributing information. At Supercell, Paananen sends a daily company-wide email with key performance indicators to all employees so that nobody is left in the dark. He explains, “It isn’t restricted to executives, it is the same information released at the same time so we can all figure out on our own what is needed.”

Transparency is one of Automattic’s most prominent values. Beau’s team uses iDoneThis to keep on the same page on what everyone’s working on and to gauge progress all in one place, which helps align his team who’s distributed across multiple time zones. In addition, roughly 80% of all internal communication at Automattic takes place on its P2 blogs, which are organized variously by function, teams, and projects and run on WordPress’s own real-time theme. Rather than information getting hoarded away, decisions and discussions are documented, shared, searchable and viewable to everyone in the company.

When everyone has the knowledge they need at their fingertips, they don’t have to wait around to get to work or make decisions, they can just do it. Distributing information also means distributing power, and sharing knowledge helps align small teams together.

* * * *

People need autonomy, mastery, and purpose to be sustainably motivated and engaged at work, as Dan Pink describes in his book, Drive. Companies like Supercell, Spotify, and Automattic show how Pink’s insights can apply to create not just intrinsic motivation for individuals but people management and collective focus at an organizational level.

People in cellular, agile small teams thrive on autonomy and mastery — which are self-centered elements — but they are also guided, connected, and even elevated through purpose, which Pink describes as “our yearning to be part of something larger than ourselves.” By definition, as organization, there should be a collective purpose, but it’s often unclear or diluted through things like unhealthy politics, mismanagement, or even being at odds with the people you hire.

In building and scaling organizations, communicating, refining, and helping people carry out that purpose is vital to creating good citizens in your work ecosystem. Like pods and squads and cells, it’s about the yin and yang of holding the individual and the collective in your mind at once and thinking about how you can grow together. Supercell’s philosophy is actually a reminder that we’re all made of smaller stuff, that small seeds can grow into giant trees, that small cells and pods can grow, in the right conditions, to achieve greater things.

Credits: Check out Kniberg explaining Spotify’s engineering culture in this video. You can find the alignment/autonomy matrix in his slides here.

3.5. Case Study: How to Get Stuff Done without Bossing Around

The availability of seed-stage funding today means that there are a ton of first-time entrepreneurs out there assembling teams and building companies without any experience running a team or managing people. Building a team in this environment is especially difficult because funded companies typically grow teams prior to sustainability or product-market fit. It’s hard to steer the team in the right direction when you yourself don’t quite know what to build.

Naval Ravikant at AngelList has blogged about “Building a team that ships”, describing his assembled team as “self-managing people who ship code.” Naval calls this peer management: one person per project (with help from others as needed), no middle managers, and individual choice on what to work on using accountability is the rudder. In his words: “Promise what you’ll do in the coming week on internal Yammer. Deliver – or publicly break your promise – next week.”

At iDoneThis, we’ve seen peer management as an effective approach to take for the young startup CEO. We’ve worked closely with many first-time entrepreneurs like Danny Wen at Harvest and Tobi Lutke at Shopify who have succeeded in building unique, quirky, and profitable companies by empowering individuals at their companies to manage themselves and each other to build out great products exceeding a high standard of excellence. Here are some keys to effective peer management that we’re seeing.

Systemized Accountability

Skillshare uses a system called Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) to systemize accountability. Every individual is responsible for company objectives, which are broken into measurable bites in the form of key results, resulting in alignment within and accountability throughout the team. At the end of every week, month, and quarter, individuals measure themselves against their OKRs to evaluate performance.

OKRs have a rich history in building great tech companies, going back to Andy Grove at Intel in the 1980s and what he called “Management by Objective.” Drawing a fundamental distinction between output and activity, Grove’s use of the word “objective” involves dual meanings. Output is both the objective and something that’s objectively measurable, while activity is a black box. An engineer at heart, management by objective was Grove’s way of bringing scientific and engineering principles to management. OKRs have since been embraced by tech giants like Google and Zynga and spread throughout the Valley and to the broader tech world. At Salesforce, they do V2MOMs (vision, values, methods, obstacles, and measurement); at Yammer, they do MORPHs (mission, objectives, results, people, and how did you do); others use KPIs (key performance indicators). While the acronyms may vary, the general principles hold true.

To Mark Pincus, OKRs are the solution to the basic problem that’s at the heart of many a founder’s anxious and sleepless night: how “to keep everybody going in productive directions when you’re not in the room.” Every individual has one objective, and they are the CEO of that objective, entrusted with authority and accountability for their objective and the key results necessary to get there.

Individual Data Tracking

“Do things, tell people. These are the only things you need to do to be successful.” When individuals are CEOs of objectives, goals, and projects, they need a way of measuring the intermediate progress and activity of themselves and their peers. As with the quantified self movement, tracking progress — writing it down — leads to reflection, knowledge, and betterment.

In old school, hierarchical companies, information that passed down to employees or up to executives had to travel through middle managers and that created a single-point of failure anti-pattern. You had to rely on your manager to get information and also to market your accomplishments upward to upper management and the executive team.

Where individuals manage themselves and each other in a peer management environment, it’s vitally important that everyone gets the requisite information flow they need to do their jobs and that they have channels to market their own accomplishments and results.

The system of snippets adopted at Google is an example not of big brother monitoring, but of empowering individuals to see everything that’s happening in the company so that they can find their niche in the company and contribute. You get a weekly email that asks what they did last week and what they plan to do in the upcoming week. Replies get compiled in a public space and distributed automatically the following day by email.

The power of snippets is in gathering data to demystify the black box of the notoriously fuzzy production process — in which raw material turns into output with the application of labor — and makes progress possible to measure, analyze, and recognize. It makes sense then that peer management environments tend towards transparency, meritocracy, and individual professional fulfillment. Companies on the rise like Shopify and Harvest track and celebrate their daily accomplishments with a daily email from us here at iDoneThis.

Fit as a Deal Breaker

In company cultures of extremely high personal autonomy, fit is paramount because it reduces friction in every interaction. Companies like Valve and Github tout bossless cultures. Stripe is building a world-class team and every employee can veto a potential hire.

While fit can be tested by hiring a candidate first as a contractor, fit often amounts to guesswork based on intuition and impression during interviews. Peter Thiel said PayPal once rejected a top-notch engineering candidate because he said during an interview that he liked to play “hoops,” and a PayPal engineer does not play basketball, much less “hoops.” The wisdom of that decision is unclear, but that decision process no doubt solidified a sense of self in the team.

Fit is about an ever-solidifying sense of self as much as it is about bringing on like-minded people, and that sense spawns canonical stories and processes. Carwoo is a company that’s a little weird, so they ask every interviewee how weird she thinks she is on a scale of 1 to 5. There is a right answer. 3-4 is the sweet spot a weird person who is self-aware.

Wistia is a company that highly values its culture and the unique identity it has built. Co-founder and CEO Chris Savage finds that combination of autonomy, culture, and fit becomes “a competitive advantage”, as Wistia hires more people, “the culture of the company should get stronger because we’re hiring for values that the company believes in, and people with those values should make it stronger.”

As work gets automated and outsourced, self-directed, creative work is required in ever-increasing degree. Peer management not only makes us more efficient, but it builds a workplace that enables — as Dan Pink describes — autonomy, mastery, and purpose that makes work fulfilling and joyful.

4. The Inherent Fairness of Salary and Performance Transparency

It’s been the system of getting a new job since time immemorial. You go through the application rigamarole. You’re interviewed multiple times, and every time, you pass muster. Finally, they’re ready to make you a job offer. They send it your way, and you take a look — it’s another lowball number. What do you do?

It’s been the system of getting a new job since time immemorial. You go through the application rigamarole. You’re interviewed multiple times, and every time, you pass muster. Finally, they’re ready to make you a job offer. They send it your way, and you take a look — it’s another lowball number. What do you do?

Startup founders often think of the lowball offer as a harmless invitation to negotiate, but to Steve Newcomb, founder of Famo.us and Powerset, it’s one of the dumbest things that you can do in recruiting engineers. And the worst thing that can happen is that the engineer accepts your lowball offer.

That’s why in his companies, Newcomb uses an unconventional but powerful tactic. Incoming engineers actually aren’t allowed to negotiate their salary — they get whatever is determined by the company’s salary formula.

4.1. The Inevitability of Salary Transparency

During his time working with engineers, Newcomb has noticed that engineers often don’t negotiate well or don’t want to negotiate. In contrast, founders “are almost by nature programmed to negotiate everything.” This creates a major mismatch that can result in founders taking advantage of engineers on salary.

The catch is that inevitably, the engineers, “who all have different deals, get drunk one night” and share how much they make. The founder’s perceived short-term gain has just killed fundamental trust and morale across his company when engineers find out they’re getting paid differentially for the same job. An engineer may not negotiate salary, but she knows when she’s being treated unfairly and will leave as a result.

What you’re left with is an engineering organization that’s good at negotiating, not engineering. In other words, you have a hiring process that reflects the perversion of the process, not merit.

4.2. How to Make a Salary Formula

Because engineers should be hired for talent rather than negotiating skill, Newcomb decided to remove all negotiation from the hiring process. It’s a bit paradoxical, but Newcomb set out to create a more fair hiring process by removing personalization and wiggle room.

Here’s what he advises for creating a rational, objective hiring plan:

- Outline 10 levels of competency per talent type; i.e. one for each type of engineer, one for designers, one for product people and so on.

- Create your high and low salary bookends for each competency, which may be unique depending on your industry.

- Then create 10 levels of salary for each competency: Junior 1-3, Mid 1-3, Senior 1-3, and a VP. Then all Junior 2 engineers would have identical salaries, as would all senior 3 engineers, etc.

Then when it comes to making a job offer, all you have to do is show them the spreadsheet, explain the rationale, and show them where they fall.

In Newcomb’s experience, engineers will actually thank you for not forcing them to negotiate, and you’ll create consistency, fairness and transparency in salary across your organization.

* * * * *

For companies like Buffer, creating an objective and fair salary formula is the starting point for total internal and external salary transparency. They not only have an internal spreadsheet with everyone’s salary and the salary formula, they’ve shared it with the world.

To Newcomb, this extreme measure makes total sense because it “heads off at the pass that drunken disclosure scenario that always gets someone pissed off or quietly erased.” It’s about not being, in Newcomb’s words, an “ass-hat” founder who tries to take advantage of his team. Rather, transparency reaffirms trust and lets us focus on doing our best work instead of worrying about whether we’re getting a raw deal.

Illustration: Aidan Jones

4.3. Case Study: Google Performance Reviews

This post was written anonymously by a current Google and former Microsoft employee. It details the author’s perspective on her first-hand experience with Google’s performance review system.

“Confidence… thrives on honesty, on honor, on the sacredness of obligations, on faithful protection and on unselfish performance. Without them it cannot live.” –Franklin D. Roosevelt

Institutions are built on the trust and credibility of their members. This maxim holds true for employees and their employers just the same as it does for citizens and their government. Whereas the electoral process in modern democracies allows you and me to rate our government’s performance, performance rating systems make employees the subject of evaluation. In both cases, however, faith in the integrity of the process is the only thing that ensures order.

Managing a performance rating system that motivates, rewards, and retains talented employees across an organization tens of thousands large is a grueling, never-ending challenge. How does an organization balance values core to its DNA and its continued success — merit, openness, innovation, and loyalty — all while maintaining perceptions of fairness?

I’ve worked at both Microsoft and Google and seen both tech giants fight this battle with complex formulae, peer awards, and strict curves.

Numerical ratings were originally born out of a desire for precision. Performance buckets were born out of an inability to defend the precise scores. As of November 2013, Microsoft eliminated its forced curve rating system. And in April 2014, Google followed suit.

All four performance rating schemes follow a similar cadence: employees are given a rating relative to their peers on a quarterly basis. This is done in secret and potentially never shared with employees. On a semi-annual basis summary assessments are shared with a selective set of examples (of work and behavior) that articulate and reinforce the rating. Then employees are made aware of the bonuses, salary raises, and stock grants they will be awarded. The rewards are decided unilaterally regardless of the dialogue that takes place during the review, and next chance to check in and reassess is six months away.

First-Hand Observations

As someone who has lived through cycles of the ever-evolving performance evaluation and rating mechanisms at these tech giants, a few observations emerge:

Forced curves undermine the spirit of collaboration and foster a mindset of hoarding pie instead of expanding it

There are particular specialized organizations that benefit from having a defined numerical goal. For example, a quarterly sales quota is a very clear measuring stick, as are portfolio returns, bugs resolved, or customers satisfied. But absent specific, level measures of productive output, large firms face the uphill battle of linking performance to rewards.

When you force fit a curve to the array of employee responsibilities, which vary in scope and complexity, it becomes virtually impossible for one lowly employee to pinpoint what distinguishes “good” from “poor” or “great”.

I’ve found myself asking, “Did I score well because I put in the hours or because I got an easy draw?” Or, “Is managing a profitable line of business more merit worthy than building a floor for a failing business?”

In my experience, people managers suffer through this ambiguity just the same. Despite the wealth of data they have about their direct reports, they’re unable to articulate the rationale (or broader context within the cohort) underlying the numerical scores they assign. And in the absence of transparency or an understanding of how individual contributions compare to team success, self-preservation rules supreme.

And even with the recent moves away from strict numerical curves, there remains a finite pool of awards to be distributed, which doesn’t reflect the mentality they’re trying to foster.

Celebrating performance through evaluation cycles (quarterly, semiannually, annually) creates a sense that every day work does not matter

The climb toward credible ratings grows steeper when you divorce an accomplishment from recognition with an annual or semiannual review. The emotional impact of a successful presentation or a new policy is nowhere to be found in a set of six month old notes. Worse still, seeing changes to compensation or a performance rating system in response to months old polling data address past concerns (and possibly the concerns of past employees).

Even data-rich, data-loving companies shy away from being transparent about how they arrive at individual ratings which produces a perception of arbitrary assessment and a false notion of precision

How do employees adapt and improve if they aren’t working at the trading desk or privy to examples of exceptional performance? They turn to Glassdoor, HR brochures, or worse of all, personal anecdotes to bolster their own assessment of whether they are receiving a “fair” deal. Unfortunately, not one of these third party sources has the nuanced understanding of an employee or his/her team necessary to provide context. What’s often left is a broken, trust-less relationship.

Performance rating systems are reactive and intended to buoy the ship against alarming trends in survey data and rates of attrition; improvements and tweaks are subject to lengthy implementation cycles

Employers seek to improve their performance rating systems and do so by soliciting regular feedback from their employees. The intention is that a system designed in collaboration will better serve all and engage employees. Where these good intentions run awry is at the implementation stage — it takes at least one quarter for to synthesize feedback and evaluation potential changes. The feedback loops for employee performance as well as the performance review system are out of sync with actual job performance and employee sentiment.

How to Do Better

So what can these firms do to win the war for credibility? Be transparent. Throw open the doors and share the notes. Make measurement and compensation public. Have peers drive the rating process. The power of transparency is well understood. There are already measures in place to build engagement among employees and alignment within teams:

- Empowering employees to reward one another

- Have everyone share in company profits (e.g. stock awards or profit sharing)

- Create awards for exceptional team performance (e.g. working across divisions or elevating the division through combined efforts)

- Pool risk vertically (e.g tying manager performance to team performance)

Increased context and knowledge builds comfort and trust for employees and managers alike. When employees know how they’re measured, there’s less room for suspicion. And when they know can connect the dots between individual performance and team success, there’s greater job satisfaction.

Ultimately, the goal of a performance rating system is to reward and retain capable employees by keeping them happy and feeling like they have a fair deal.

Transparency goes a far way toward lending credibility to the process and building commitment to the company, but it isn’t a silver bullet. Giving employees greater flexibility in what they take on and the efforts they lead also builds a sense of ownership and commitment. Opportunities such as 20% projects (wherein employees spends 20% of their time working on something about which they’re passionate) or cross organizational initiatives (e.g. building a volunteering program) are excellent examples of empowering employees through choice. But there’s room for this notion of self direction to go even further — a completely open allocation (e.g. 100% self directed time) or letting employees choose their manager are two programs I would certainly sign up for.

What it boils down to is that employees want to know how they are being evaluated and want to know that they’re making conscious choices. Because while you vote with a punch card at the election booth, in the workplace you vote with your feet.

Photo: Denis Cappellin

4.4. Case Study: Stop Repeating the Same Mistakes

We make a lot of mistakes in life, and a lot of those mistakes take place at work. Elaine Wherry, founder of Meebo, even made a mistake diary to remember and review her mistakes, such as time management and perfectionism issues. “I wanted to be able to reflect on them later,” she explains, “so I wouldn’t beat myself up during the week … It was a way to get more sleep.” As she saw her employees make many of the same mistakes she did, the diary developed into a manual to share what she learned with others.

Luc Levesque, founder of TravelPod and General Manager at TripAdvisor, decided to guide his employees with a boss blueprint. Luc shares his particular values, dislikes, and quirks to prime new employees for great performance in short order. With swift, effective communication rather than protracted information asymmetry, employees — and the company as a whole — are able to sidestep a period of trial and error, as well as lots of trials, tribulations, and stress.

Luc’s candid approach to managing people extends to his efforts to build a transparent work environment, turning management into a conversation. Frequent feedback through daily syncing tools and monthly reviews have taken the ceremony and often fruitless, demotivating effect out of the more formal review process and normalized the discussion around setbacks and mistakes. He explains, “When something happens that deserves to be talked about, it’s so much easier to have that conversation on a thirty-day basis. It’s not a big deal. It’s just a conversation, which is what we’re supposed to be doing as leaders anyways.”

The monthly review was actually a concept recommended by Luc’s business coach. “I’m a big believer in coaching, just because I’ve seen the results,” says Luc. “Our results have been very good for six years in a row, and I attribute a lot of that to the team and the help that my coach has given me.”

When you have something like a blueprint, a manual, or people like managers and coaches to guide you along the way, you gain lessons and perspective. Too often, though, we ignore the fact that we can be our own beneficial guides and coaches, make our own blueprints. Few people take time to pause, reflect on and grow from mistakes, and take stock of the ever-evolving questions of what’s working, what’s not, what we want, what we don’t, and why.

Maybe it’s because pausing seems unproductive, too much like idleness, but the opposite is true. Your mindset toward mistakes can influence your performance. Research shows that people who think they can learn from their mistakes pay more attention and improve performance after making them. And learning, driving toward goals, and getting better at things — which are undoubtedly productive — requires quiet self-reflection.

We will continue to make mistakes; the important thing is that we can stop repeating them. What’s more, we do things that are smart and magnificent — let’s repeat those. Let’s help others and ourselves grow by building a practice and culture of slowing down to review the past and contemplate how that fits into our present and future. In doing so, we arm ourselves with the confidence to try and innovate, the resilience to flourish from failure, and the knowledge and courage to make an impact.

5. Work In Public

The peculiar challenge of knowledge work is that so much of it takes place in our heads and out of sight. In contrast to the era of factory work, knowledge work is nowhere near as visible. You can’t discern the state of progress by looking at tangible output or product.

This poses a particular problem for managers, whose job it is to support their employees and enable progress. You can’t properly manage what you can’t see. Otherwise the result is directives and orders that don’t make sense, veering toward irrelevance and away from the reality of the situation. Leading blindly without understanding the status of projects and the context in which people are working makes as much sense as managing a production line without seeing the state and quality of a product as it is being assembled.

Show and Tell Your Work

The solution is to encourage and cultivate showing your work, or put another way, working out loud. Communicating what you’ve done is vital to moving things along, and it actually should be the other half of your job.

The benefits are clear. With transparency and communication of information, teams and organizations can improve productivity because they are able to manage operational efficiency. With the ability to see all the moving parts, you can figure out how to work better. Then, the opportunity opens up for improving planning and methods, collaborating and striving for more dazzling results, and having a common basis and drawing board to truly innovate together.

Why We Hide

The interesting thing about showing your work, though, is how resistant people — including both the managers and the managed — can be in implementing the practice. The underlying reason for this hesitation comes down to how managers hold people accountable, because it changes how people perceive the intent behind the effort to be more transparent.

Bad managers impede and inhibit progress in two ways. One is the traditional school of managing people that fails to deal with real progress at all. That school subscribes to the mistaken belief that management is about oversight and monitoring for the purpose of Big Brother-type control, thinking that you make things happen by paternalistic brute force.

The other approach is one of disengagement in order to keep the positive image of being liked, thinking that this lack of confrontation and involvement is what is necessary to keep the wheels greased. The crazy result is that one of out every two managers fail to keep people accountable.

Employees then feel resentful of losing autonomy and substantive feedback and become increasingly disengaged, feeling like useless cogs in the machine.

Such managerial failures in approach to accountability is thus why employees themselves can view transparency with such suspicion. As with personal relationships, there’s a difference between transparency for the purpose of engagement and open communication as opposed to for the purpose of coercive oversight. And transparency becomes futile when information goes nowhere or falls on deaf ears.

The Courage To Be Accountable

At the end of the day, both the managed and managers don’t want to feel vulnerable. For employees, transparency can seem a risky business of putting themselves out there, with the potential to look weak or ineffective or ignored, especially in situations with bad management. For managers, transparency and accountability means having difficult conversations, truly getting involved with their teams as people and their work, and getting used to the uncomfortable notion that management isn’t so much about control but support and facilitation.

Accountability does require visibility, but we should never treat people like faceless cogs in a machine. Working out loud should not produce more constraints and traps but more autonomy. If managers are doing their job of helping people make progress, people will want to show their work and together cultivate a vibrant company culture of openness, fruitful feedback, and deep engagement.

Images: [1] Shreyans Bhansali; [2] Frits Ahlefeldt-Laurvig; [3] Joel Ormsby>

5.1. Case Study: Why Getting Personal Matters for Getting Professional

Even if transparency is one of your official organizational values, how do you actually make that come true?

Karma has a company culture of openness and sharing, one that reflects its mission to make connecting to the internet easier for everyone. That philosophy of accessibility permeates the company — whether in sharing their journey with their customers, providing weekly — yes, weekly — updates to their investors, or how they get stuff done together.

Company culture isn’t what is written on a poster or slide deck but what happens day-by-day. And what the Karma team has figured out is that transparency doesn’t just happen by itself. The kind of information-sharing it requires depends on people’s willingness to be open with each other, day in and day out — and one of the best ways to do it is tell each other about their day.

The Power of Storytelling At Work

The Karma team seems to intuitively understand how to share with each other, and they do so as a distributed team, with an office in New York and people out in Amsterdam, South Korea, and San Francisco.

What helps them stay connected is by writing asynchronous email updates every day about what they’re up to in iDoneThis. Instead of writing dry, humdrum items that sound like checked-off errands on a to-do list, they approach the updates as an opportunity to share stories of what’s going on and what stood out about the day — including what you got done, funny things that happened, or a customer email that makes or breaks your day.

Paul Miller, a former journalist who recently joined the Karma team, told us how the updates can be like a serialized story. His coworker, Klaas, for example, was trying to get charts to work on Android for the longest time, and every day was a new snippet in the continuing battle. “It was the most entertaining saga,” Paul notes. “The most interesting things are these internal struggles that people have.”

Work Narration Helps People Do Their Job

What the Karma team is doing is narrating their work – describing their experiences and presenting that story to their team. Instead of the painful, artificial process of filling out formal status reports, or having managers monitor their every move, it’s the employees who are the authors, the ones in charge of what they tell and how.

In fact, for Paul, the updates are an opportunity to practice his craft, “As a writer, I’m just always performing when I’m writing. I live for the likes. A like in iDoneThis means more to me than a retweet.”

As Drake Baer writes, narrated work allows people, especially managers, to know what everyone’s up to without spying or nagging them:

Intensely smart management thinker Dion Hinchcliffe calls it narrated work: …[C]reate a palette for people to describe the work they’re doing as they’re doing it, creating a record of all the things that get done, all without eroding the foundation of creativity: autonomy.

And that’s how Karma gets stuff done as a fast-moving, adaptable startup team. CEO Steven van Wel explains, “We give people a lot of freedom to do what they want to do. Everyone has a ton of responsibilities and within Karma, responsibility also means transparency” — including “making sure that everybody else knows what you’re doing.”

The Team that Eats Together

Narrated work allows a glimpse beyond what people are doing into how they’re doing. This transforms what Harvard Business School professor Teresa Amabile calls the “inner work life” (the “constant stream of emotions, perceptions, and motivations as they react to and make sense of the events of the workday”) into common knowledge.

Getting people to share that inner work life and other personal stories doesn’t come naturally. According to Steven, one key to making that possible is their daily family-style team lunches.

In Amsterdam, work lunch is a communal process. People buy groceries, make the food — often sandwiches — set the table, and eat together. When the Karma co-founders first arrived to New York from, they followed what everyone else was doing and ate lunch at their desks. But Steven had to put his foot down at the misery of it all: “No way! I’m behind my desk for eight to ten hours, and I need to get away.”

Now Karma has taken up the Dutch lunch tradition, New-York style. Every day, everyone orders food on Seamless (paid by the company) — and sits down to eat together, family-style. This time isn’t for discussing work at all but everything else, from funny things on the Internet to whatever’s going on people’s lives, like the inevitable Ikea-themed stories that popped up when multiple team-members were moving at the same time.

Getting to know people on a personal level seems like it could be distracting or unprofessional but it actually provides an important foundation of learning how to communicate with each other.

* * * * *

Many co-workers eat lunch together, but for Karma, the ritual is a deliberate part of a larger culture to build both personal relationships and an open way of working.

Narrating work, telling personal stories, and sharing your inner work life are inherently vulnerable acts that can’t happen without a certain level of trust and comfort. Thanks in large part to daily interaction, work narration, and team lunches, Karma team has developed a foundational camaraderie that makes it possible to support, share, and do great work with one another.

5.2. Case Study: Write Your Own Story

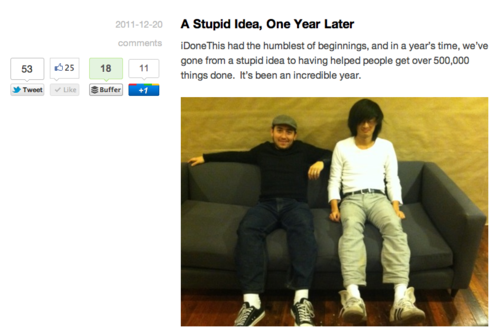

Every milestone is an opportunity to attract attention to your startup because you have a piece of “news” — a new piece of noteworthy information that no one else but you has.

When you have something to announce, conventional wisdom says to go to the press and blogs with your story because they (1) have distribution and (2) are expert in crafting a story. In the past, we’ve offered nuggets of news to journalists as exclusives, and we’ve gotten written up by Betabeat and The Next Web this way.

However, we’ve recently experimented with writing our own story on our own blog, telling a narrative that’s personal and shows how we work behind the scenes, harnessing the power of social news for distribution — and that has resulted in our all-time one-day high for traffic and 1,000+ signups, more than double the signups resulting from our press coverage. Through that experience, we’ve learned the importance of writing your own story and turning transparency and narrative into a competitive advantage.

The Old Way

Here’s the short email I sent to Courtney Boyd Myers at The Next Web when we passed 200,000 daily dones. She had written about us once before, and we had a great experience with that early press coverage.

Hey Courtney, we’ve crossed a significant milestone here at iDoneThis and I wanted to give you an exclusive on it because you kicked things off for us with your article back in January.

Our users have gotten 200,000 things done using iDoneThis.

I’d love to talk with you about what people have gotten done. One person used iDoneThis to finish his Ph.D. My co-founder used iDoneThis to go from the couch to finishing Tough Mudder. Another guy even used iDoneThis to propose to his girlfriend.

Let me know if you’re interested in writing about us!

She agreed and asked me some questions, and a few days later, we had a story: iDoneThis announces its first milestone: 200,000 completed tasks.

We got 400+ signups from the article, some traffic, social media buzz, and pats on the back from friends.

Writing Our Own Story

When we hit 500,000 daily dones, we decided to do something a little different. In addition to getting press coverage about how we hit 500,000 daily dones, we wrote our own story on our blog that gave a behind-the-scenes look on the year leading up to hitting our big milestone.

The Next Web story got around 1,000 people to click through, producing over 400 signups. Our blog post got 3,000+ people to click through, resulting in just over 1,000 signups.

Lacking a distribution network for our post, we turned to Hacker News. Social news sites like Hacker News are a democratic force, giving everyone an equal say, 1 upvote, in determining the placement of an article.

That’s not to say that social news is a meritocracy. Most people I know who have turned getting to the top of HN into a repeatable process use an email list to request upvotes whenever they post a piece in order to get the requisite momentum to reach the top. Nevertheless, HN is still one person, one vote, instead of one person positioned as a gatekeeper, as in the press. Plus, quality is a big determinant in an article’s staying power once it’s placed near the top of the main page.

Press is obviously press-centric, curated by editors, whereas social news is centered around the individual reader. When you get press coverage, you build a relationship with the press — for instance, getting to know the journalist who wrote about you — and you’re more likely to get written up by that journalist and publication again.

When you write your own story, you build a relationship with the readers themselves. They follow you on Twitter and “like” you on Facebook, creating subscriptions, essentially. Through these channels, you can reach them again, leveraging your HN email list into a Twitter and Facebook following or, put differently, your own distribution network.

Both create a repeatable process for driving traffic to your site, but the latter is more reliable and the content it demands is more personal and, I think, compelling. Ultimately, “news” most often refers to funding announcements, new feature releases and the like — not, for instance, a description about the clever way that you solved an interesting problem. Writing your own story is your opportunity to establish your MVP (Minimum Viable Personality), show the world who you are, and make that your competitive advantage.