This post was originally published in 2017, and we’ve since updated it with new research and examples.

You’re swamped with a huge project when your boss suddenly asks you to complete another urgent assignment that’s due tomorrow. Your heart’s beating a mile a minute, and you’re wondering how you’re going to get this all done. But, somehow, you’re going to try to make it work.

Too much stress will overwhelm you, but too little stress leaves you bored and unmotivated. The right amount of stress motivates you to succeed instead of making you crack under pressure.

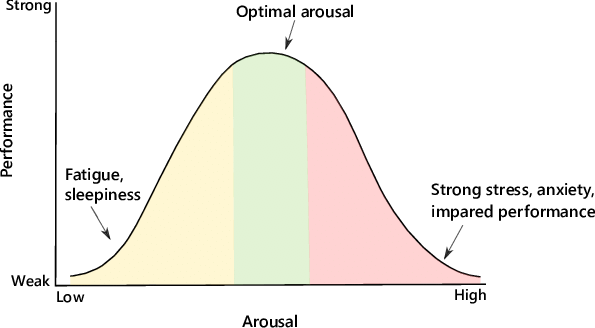

Your tendency to thrive or choke under pressure is ultimately based on the Yerkes-Dodson Law: Moderate stress up to a certain point can actually improve your performance. But beyond that point, your performance suffers.

Stress management is built into your brain’s chemistry. Here’s the science behind your body’s stress levels, so you can maximize your productivity.

Stress and Performance

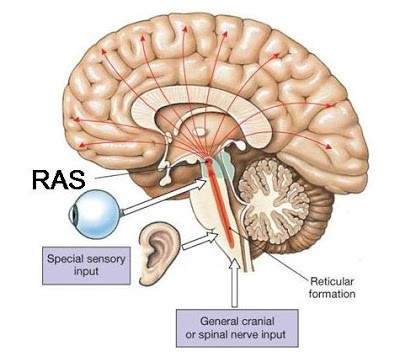

Imagine that you’re focused on sending a few quick emails before you head out for lunch. You’re able to zone out of your surroundings until you hear a coworker say your name. Your attention quickly shifts to your coworker. That was your reticular activating system at work.

The reticular activating system (RAS) is a pencil-thin piece of your brain that sorts through thousands of messages every second. It’s like a personal spam filter, helping to determine what information is really worth your attention.

[Source]

Your RAS activity can be illustrated by what’s known as the Yerkes-Dodson curve. The RAS speeds up and makes you more alert as stress levels increase.

Your stress levels are regulated by cortisol, which works in harmony with the RAS. Too much cortisol will damage your workflow. Some cortisol, on the other hand, can make you a more focused worker:

- In the calm zone, your RAS is slowed down. You feel bored and tired and find it hard to focus on your work.

- In the stress zone, your RAS is starting to pick up speed. You feel highly active and alert. You notice increased attention and interest in your work. At the top of the curve, you are most engaged in your work.

- In the distress zone, your RAS is in overdrive. You’re super anxious and feeling totally overwhelmed by your work.

[Source]

Here’s the science behind how cortisol affects your productivity.

Moderate Cortisol Levels Maximize Performance

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi studied the most talented athletes, like Michael Jordan, and discovered a state of heightened focus that helped them stay “in the zone”:

“To pursue mental operations to any depth, a person has to learn to concentrate attention. Without focus, consciousness is in a state of chaos.”

When your cortisol is under control, you can get “in the zone” at work the same way Michael Jordan did on the basketball court. Cortisol hormones, produced by your adrenal glands, attach themselves to mineralocorticoid receptors at lower stress levels, which improves memory. You’re able to stay focused under pressure, and your memory is sharper.

When you’re at a moderate stress level, you’re in the middle of the Yerkes-Dodson curve; your cortisol levels are neither too high nor too low, and you’re operating at your peak performance (the stress zone).

Challenging tasks seem more manageable when you’re in this state of flow. Problem-solving becomes almost automatic. You’re able to efficiently move from one step to the next without hesitation.

But once your cortisol levels increase beyond this point, your productivity starts going downhill.

How increased cortisol levels damage your productivity

Elevated cortisol levels cause the RAS’s neurons to fire more rapidly, making you feel extremely anxious. Besides messing with your RAS, cortisol hormones attach themselves to glucocorticoid receptors when stress levels are increased, which interferes with memory. You become stressed and forgetful.

When you’re totally stressed out, you’re on the right side of the Yerkes-Dodson curve. Your cortisol levels are at their maximum, which corresponds to breakdown and lousy performance (the distress zone).

Too much anxiety will paralyze you and make it impossible to concentrate on your work. You’ll find yourself unable to perform under pressure.

The deteriorating effects of stress on the body

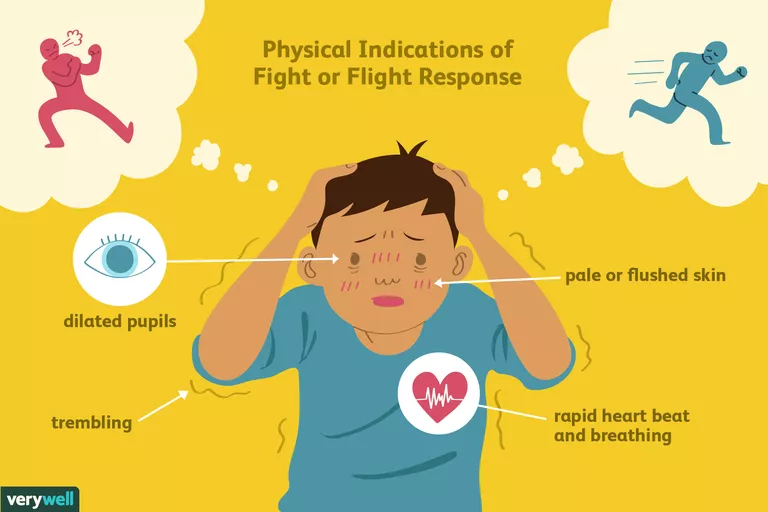

Stress is powerful because it’s flowing through a physiological system forged in our earliest evolutionary moments. When you panic, you’re returning to an emotional, mental, and physical state almost all animals regularly enter: fight or flight.

Fight or flight is the choice most animals face when they encounter a threat. If a predator jumps out of the bush, an animal’s nervous system floods with stress hormones, including cortisol, and adrenaline drives them to decide between fighting the threat or fleeing from it.

For animals, this stress response is an evolutionary advantage because it can mean the difference between life and death.

[Source]

For most animals, stress is temporary: A threat emerges, they panic, they fight it or flee it, and then the stress dissipates.

A side effect of human intelligence is that threats can stay on the horizon for much longer periods—potentially forever. If your manager doesn’t appear happy with your work, for example, you could stress out for months as you wait for a performance review or for some other feedback.

Evolution didn’t prepare you for this amount of stress. It can handle intense bursts, but long, drawn-out, chronic stress can destroy you from within. Your nervous system doesn’t know the difference between predators around the corner and workplace problems months away from emerging.

The science of stress is alarming. Chronic stress can weaken your immune system, upset your stomach, and make heart disease more likely. Your memory can worsen, and depression and anxiety become harder to avoid.

Your response to stress can be even more dangerous. If your coping strategy is to eat junk food, for instance, you might damage your health even further whenever you get stressed. Bad coping skills combined with stress could encourage a downward spiral that’s difficult to escape.

Avoid burnout and the long term effects of stress

A good weekend won’t cure severe, chronic stress. You might relax a little bit, but if your body and mind are still in stress mode, then recovery can be more difficult. And the long-term effects of stress can be dire.

The more your stress system fires, the easier it is to trigger. If every workday creates stress, you’re training your nervous system that every day is full of predators. Before you even encounter a stressor, your body and mind will tense up, readying itself for threats always around the corner.

This defensive pose can lead to burnout if unchecked.

According to Anne Helen Petersen, burnout is fundamentally different from mere exhaustion:

“Burnout is of a substantively different category than ‘exhaustion,’ although it’s related. Exhaustion means going to the point where you can’t go any further; burnout means reaching that point and pushing yourself to keep going, whether for days or weeks or years.”

Stress will tire you out; working while stressed endlessly and without resolution will lead to burnout.

If stress dominates your daily life, your mental health will suffer. Burnout is when you’ve trained your body to normalize stress. Your well-being becomes dependent on your ability to complete tasks—so much so that when there aren’t tasks to complete, you’ll seek out new ones.

Josh Cohen, a psychoanalyst, writes:

“You feel burnout when you’ve exhausted all your internal resources, yet cannot free yourself of the nervous compulsion to go on regardless.”

Stress goes from being a visitor to a companion. And once you normalize its presence, it is hard to get away from.

How to reduce short and long term stress

Chronically high levels of cortisol can actually cause your brain cells to malfunction. But it’s possible to control your cortisol levels and reduce harmful stress.

The ideal theory of stress management would be to find the optimal amount of stress for each person. We each have a unique stress threshold, which partly depends on our genes, personality, and life experiences.

Although you can’t exactly calculate your tipping point, you can lessen your chance of getting there by lowering your cortisol levels. Here are several practical suggestions to reduce cortisol production and lower stress over the short and long term.

Short-term stress reduction

When the day is getting overwhelming, take the time to reduce stress—even if it’s temporary.

- Take power naps. Taking a short nap during an afternoon break is one of the quickest ways to reduce cortisol. A NASA study of military pilots and astronauts showed you can improve performance by 34% and alertness by 100% with a 40-minute nap.

- Visit a park. Researchers conducted studies in 24 forests across Japan. They sent some people to a city and others to a forest and then measured their stress levels. They found that simply surrounding yourself in a forest environment lowers cortisol, blood pressure, and heart rate.

- Listen to soothing music. A study at Ruhr University Bochum revealed that participants who listened to Mozart or Strauss had notably lower cortisol concentrations than those who listened to more high-energy pop.

- Get motivated. When work gets overwhelming, give yourself the time to take a break and find some inspiration. A challenge can seem insurmountable, but with the right productivity advice or motivational push, you can get through the day.

Long-term stress reduction

To make stress truly manageable, you should combine these intermittent activities with regular practices that diminish all types of stress over the long term:

- Exercise regularly. According to research published by Harvard Medical School, about 30 to 40 minutes of moderate exercise a day (such as walking) can balance cortisol levels, manage blood sugar levels, and improve sleep. The key is to avoid overexerting yourself since this can increase cortisol.

- Expand your toolset. If you’re having trouble keeping up, explore which task management tools and business applications might make your work more productive and well-organized. If you’re not in the office often, think about adding tools that keep you in the loop with the rest of your coworkers.

- Adjust your work–life balance. Your work can be both fulfilling and stressful. Even if you love your job, you need to make time to relax and spend time on other valuable activities. Take a careful look at how events like the end of a quarter overextend your workday.

- Go remote. A long commute can be another cause of stress and heightened cortisol levels. Try to convince your manager that you can work partially or fully remotely, or even consider taking a new, fully remote job.

Whether you wan to remove long-term stress or short-term stress from your life, you must know about the negativity bias that might be causing this problem. You can learn more about that in this iDoneThis article.

If you’re a manager, you can be proactive about reducing stress for your employees. Chris Zaugg, for instance, co-founder of Uptick, once found an employee coming into the office at night (when he felt most productive), leading to stressful, sleepless days. Zaugg adjusted his schedule and the employee ended up happier and more productive.

The Yerkes-Dodson Law helps you to see that everyone has a tipping point. You can use stress to maximize your performance, but it’s only helpful up to a point.

If you use good stress to your advantage, you’ll work at your peak performance level without burning out. As a manager, you can help your employees steer toward this sweet spot and avoid burning out along the way.

P.S. If you liked this article, you just might love our software. Click here to try it out.